The tragic tale of a donkey who is passed between different owners that treat him poorly resonated with many – not least Polish director Jerzy Skolimowski who still remembers the experience of seeing it for the first time, as he told Zavvi:

“I was in Paris when Cahiers du Cinema published their list of the best films of 1966.

"I was surprised to see my own film Walkover at number two, so I was naturally curious to see the movie that beat me – I went to the first screening of Au Hasard Balthazar that day.

“A lot of it wasn’t my style, but by the end, I had tears in my eyes for the first and only time after visiting the cinema. That was the lesson: I was taught that an animal can move the audience better than any human character.

"When you see an animal, it doesn’t know that it’s acting, which makes the tragic things that happen to it all the more powerful. When human actors do a scene where they die, they tend to overact – for an animal, it’s not a performance, it’s natural behaviour.”

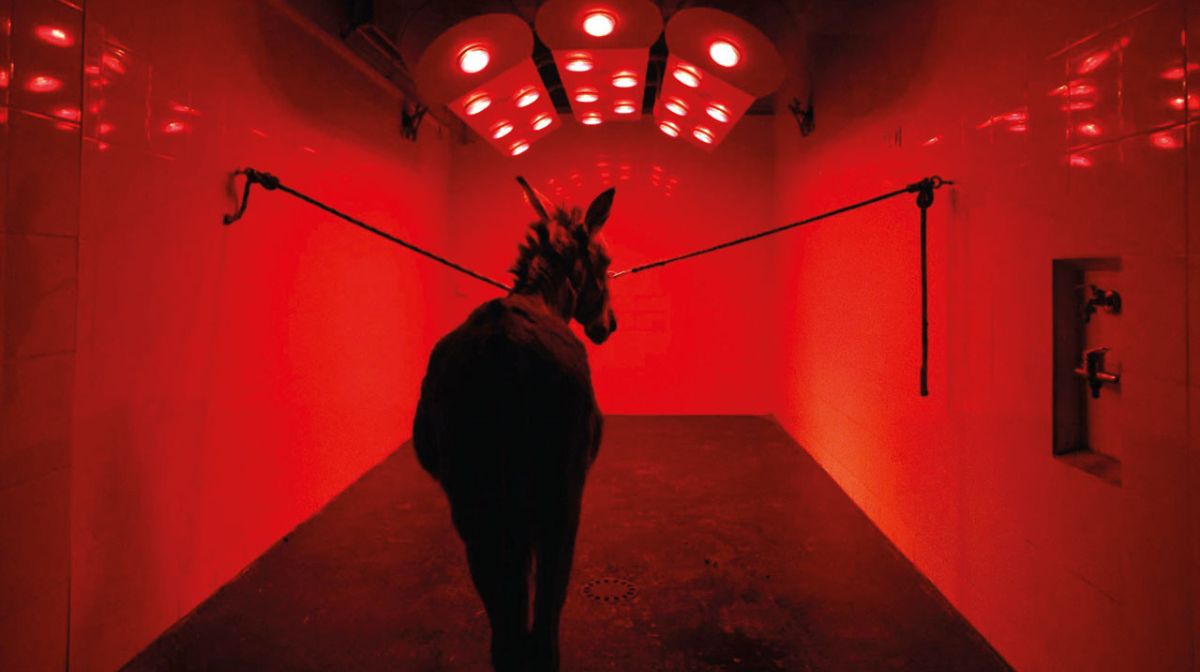

More than sixty years later, the now 84-year-old director has applied the lessons he learnt from watching Au Hasard Balthazar to EO, his stylish odyssey across contemporary Poland seen through the eyes of the titular donkey.

After leaving the circus, EO goes on an epic adventure that takes him from meeting climate activists and football hooligans to visiting the home of Isabelle Huppert.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dBwv0dW5x_g

Jean-Luc Godard famously described Au Hasard Balthazar as “the world in an hour and a half” - with EO, Skolimowski gives you it in just over 80 minutes.

The decision to make the episodic travelogue his next film was sparked by a need to move away from linear storytelling (“when I’m in the cinema, I know after ten minutes where every film is going!”), knowing that an animal character could help him create it.

“When you have a character who can’t speak, you have to look for another way of expressing what’s going on in their mind, and before we decided upon the specific animal, we knew we needed one with an expressive face. We didn’t want the usual narrative focused on a dog or a cat’s journey, and when we came across a donkey, we knew it was right. There’s an incredible potential in their eyes, which are unusually large in proportion to their body – it's strange and melancholic.

“So I was never directly inspired by Bresson’s film, but by the potential of the possibilities of the expressions of animals. I wanted to use the editorial trick of cutting from their eyes, so we can communicate what is going through their mind without ever needing exposition”.

As the old saying goes, you should never work with children or animals, although Skolimowski wasn’t particularly nervous about the scale of his challenge (“I’m quite experienced – in my household we’ve always had a dog!”). Much of their considerations instead had to be focused on finding the right animal performers who fit their specifications, which initially led them to a remote Italian village, where the film’s introductory sequence was filmed.

“The specific donkey we were looking for was of the Sardinian breed, and the problems we had were using animals which belonged to a certain place; we didn’t want to make them travel long distances to shoot for the sake of their well-being.

"On Facebook, we came across a film of this Italian guy and his donkey who perform in their village, their routine ends with the donkey pretending he’s dying and the man giving him mouth to mouth. We thought it’d be a great opening scene if we could find this guy, and on reaching out, we found they only performed in villages around where they lived, as the donkey was very fragile.

“We travelled to North Italy to film the circus scene in the donkey stable, turning it into a little arena. As you can imagine, it was quite expensive, not least because we had to pay for the whole crew to come to this small village – but that opening scene is very effective, it was worth it. It strikes you immediately: you make a connection from the very first second, before we even establish the characters”.

In total, the film shot for 26 months – and no, it wasn’t just because of the various COVID shutdowns along the way (although that certainly didn’t help matters). As the shoot was spread out across different regions of Poland, moving from the South to the North and back again due to largely shooting scenes in the order they appear, preparation for each new phase pushed everybody back to square one – as did waiting for Polish Film Institute funding along the way.

The novel coronavirus ensured that the gaps were more prolonged than they otherwise would have been, with a total of three cinematographers taking up that role due to infections during production. But the biggest issue that led to the shoot lasting 26 months was something nobody could have predicted.

“The actor playing the truck driver, he had problems passing the test learning how to drive a truck! We found it was unbelievably difficult to shoot those sequences without showing him driving – that turned out to be the most difficult challenge. We ended up waiting for him to pass him exams, and he kept failing!

“Then we had to wait for Isabelle Huppert’s availability; we needed her for three days, and she only had little windows here and there, as you’d expect. We ended up shooting her scenes on Christmas Eve, which was unusual.

"You’d expect the crew not to want to work in the immediate days leading up to Christmas, but they wanted to go on. They believed in the importance of this film to the point they agreed to work when they should have been back home with their families!”

After a mammoth shoot, filming finally wrapped on 10th March, 2022 – leaving everybody with just two months to complete post-production, as they wanted it to premiere in Cannes in May. Skolimowski and his team succeeded in their aims, winning the festival’s Jury Prize for their efforts, but it came with a price.

“I paid for it with my own health. In the last few days before we delivered the print for Cannes, we were working day and night, finishing at six in the morning, going home for an hour to walk the dog, then back to the studio to mix the sound.

"We didn’t finish it properly until two days before the screening. On my very first free day that I wasn’t working, I went out for a walk and I suddenly collapsed and hurt myself very badly – I ended up in hospital instead of in Cannes presenting the film”.

The director managed to recover in time to return for the awards ceremony a week later, thanking his donkeys and making an “eeyore” sound in his acceptance speech. Since then, it’s had a successful festival run and been selected as Poland’s submission for the Best International Film Oscar, and remains tipped as one of the favourites in the category.

The director was inspired to make EO to raise awareness about the mistreatment of animals, and the unique nature of his cinematic odyssey has succeeded in getting people talking, something which will only continue when it arrives on British screens in early February.

EO is released in UK cinemas on Friday 3rd February.

For all things pop culture, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok.