The acclaimed author, who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2017, has long been a fan of legendary director Akira Kurosawa’s indelible 1952 film Ikiru, the story of one man’s final quest to find meaning in his life.

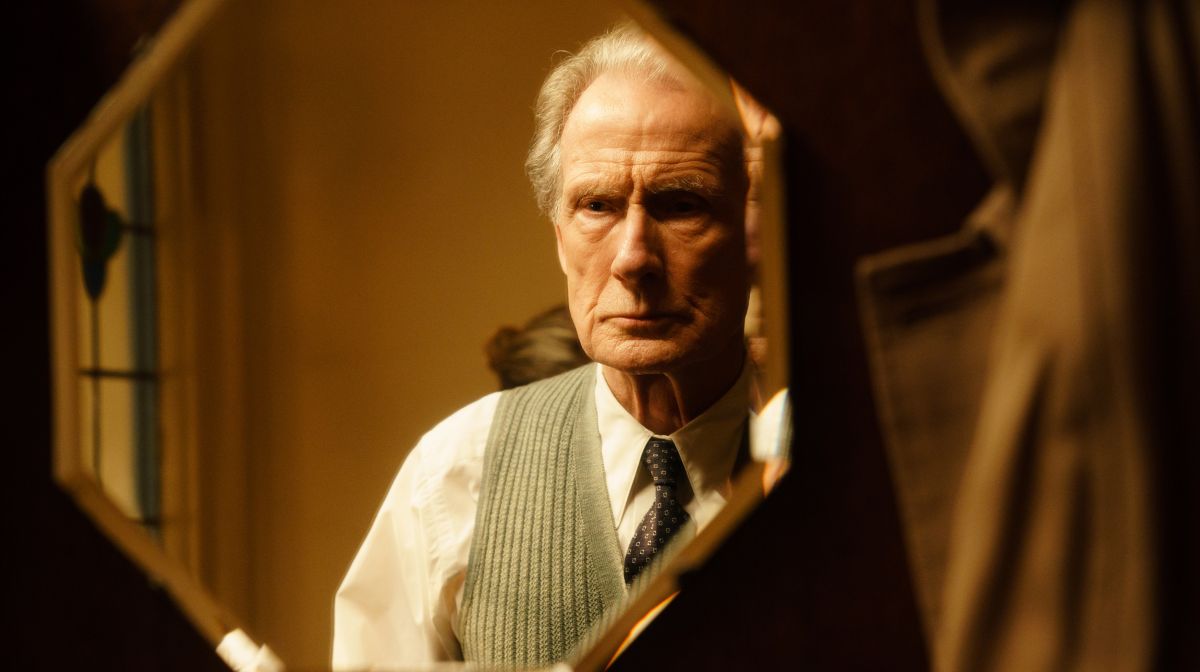

One night whilst having dinner with film producer Stephen Woolley, actor Bill Nighy dropped by for a drink, with the trio spending the evening discussing all things cinema.

In that moment something clicked for Ishiguro, who started forming an idea that would eventually turn into Living.

Speaking to Zavvi, the director of the feature, Oliver Hermanus, explained: “He wanted to make something bold that was a celebration of Bill as an actor. Meanwhile Ikiru was a film he grew up with, something he had connected with throughout his life.

"Ishiguro married those two things together asking, ‘what if I made the film I love with the actor I love?’ Woolley then told him to write that movie, saying he’ll try get Bill to do it and find a director.”

Starting work on the screenplay, Ishiguro’s vision was clear from the beginning – he wanted to reimagine Ikiru, moving it to 1950s London with Nighy in the lead role.

Whilst Ishiguro started writing his adaptation, producer Woolley began work on his two tasks: persuading Nighy to star and finding the right filmmaker for the project.

Thankfully Nighy immediately said yes, leaving Woolley able to focus on his search for a director. The only criteria on his list was that the filmmaker didn’t come from the UK, a seemingly strange choice given that Living is a British period drama about an English gentleman.

However, as South African director Hermanus tells us, this brought a new perspective to the project: “I think they were right. I have seen people not from my country make films about it, and although sometimes that work isn’t great, it does change perspective, providing an outsider’s point of view.

"Perhaps certain things become less complicated in how the filmmaker interprets class, culture, language, or race. Maybe I just cut through those things easier not being from here.”

Having been recruited for his ability to bring a new perspective, Hermanus was invited to work with Ishiguro on the screenplay, a task he admits he found challenging at first:

“At the beginning it was really hard for me to say one word as I was unsure how to contribute – I had all these ideas, thoughts, and feelings, but it was a confidence thing.

"Ishiguro eventually said to me one day, ‘you just have to tell me what you want as I’m writing a screenplay for something you are directing’.

That was a really important moment for me and in a sense gave me permission to be the director, making it a real collaboration. He worked tirelessly to perfect it and indulge my questions for months.”

Given that Ikiru is very much a film about post-war Japan, how the nation was restructuring in the face of loss, you may be wondering how the story could be moved to ‘50s London following the Allied victory.

However, as Hermanus notes, not only are the societies of Japan and Britain actually very similar, but the themes of both Ikiru and now Living are universal.

He explained: “Japan and England were countries coming out of war in very different ways, but both have a certain nature within their societies that leaves people with an inability to communicate, especially emotionally, even with your family.

"Ishiguro is fascinated with this stoicism and it’s universal, any family can have that challenge. There’s an innocence and beauty about wanting to communicate but feeling like you’re not allowed to, that’s something we can all connect with.

"It becomes emotional as we all know that felling. That permission to express yourself is something we are still negotiating today, the freedom to say what you think or feel and for it to be received, that isn’t necessarily guaranteed.”

Nighy’s stoic gentleman Mr. Williams struggles to communicate from the very start of the movie, choosing to ride in a different train carriage to be separated from his work colleagues.

This only intensifies when he is diagnosed with a terminal illness, something that completely shatters his universe, leaving Williams wanting to take stock of his life and find meaning in it.

Living therefore is a moving watch and a film that will have you reflecting on your own life as Williams looks at his. But what has Hermanus himself taken away from the experience?

The director concludes by telling us for him it’s all about Williams’ last act, to build a park for the local community of mothers: “You have to find something personal, it has to live inside of you.

"This was a harder one to get into because I didn’t have a connection at the beginning, I thought maybe they should have an older filmmaker, someone who has lived more of a life.

"But when I did really think about it, what I took away from Williams’ gesture is different to how others interpret it. I see it as an act of giving – people don’t give as much time, attention, or feeling as they could. But Williams does, he gives something to these people which is selfless in a way.

"It’s fulfilling for him, but he doesn’t want anything in return or for anyone to know what he gave. That’s what I appreciate about this movie. It’s an act that is within arm’s reach. In today’s world we can zone out and switch off from the world, but it’s important to connect.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t2L8CP31-14

To read more from our interview with Hermanus, check out the upcoming edition of our free digital magazine The Lowdown which is released on 7th November.

Sign up here to get the latest issues of The Lowdown sent straight to your inbox.Living is released in UK cinemas on Friday 4th November.

For all things pop culture, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok.