From Alain Delon’s trench coat wearing contract killer in Le Samouraï, whose approach to work is inspired by old Japanese epics, to the fast-talking, pop culture obsessed likes of Vincent Vega and Jules Winnfield from Pulp Fiction several decades later, the big screen hitman regularly changed with the times, but was almost always stylised to be the coolest guy on screen, despite his profession.

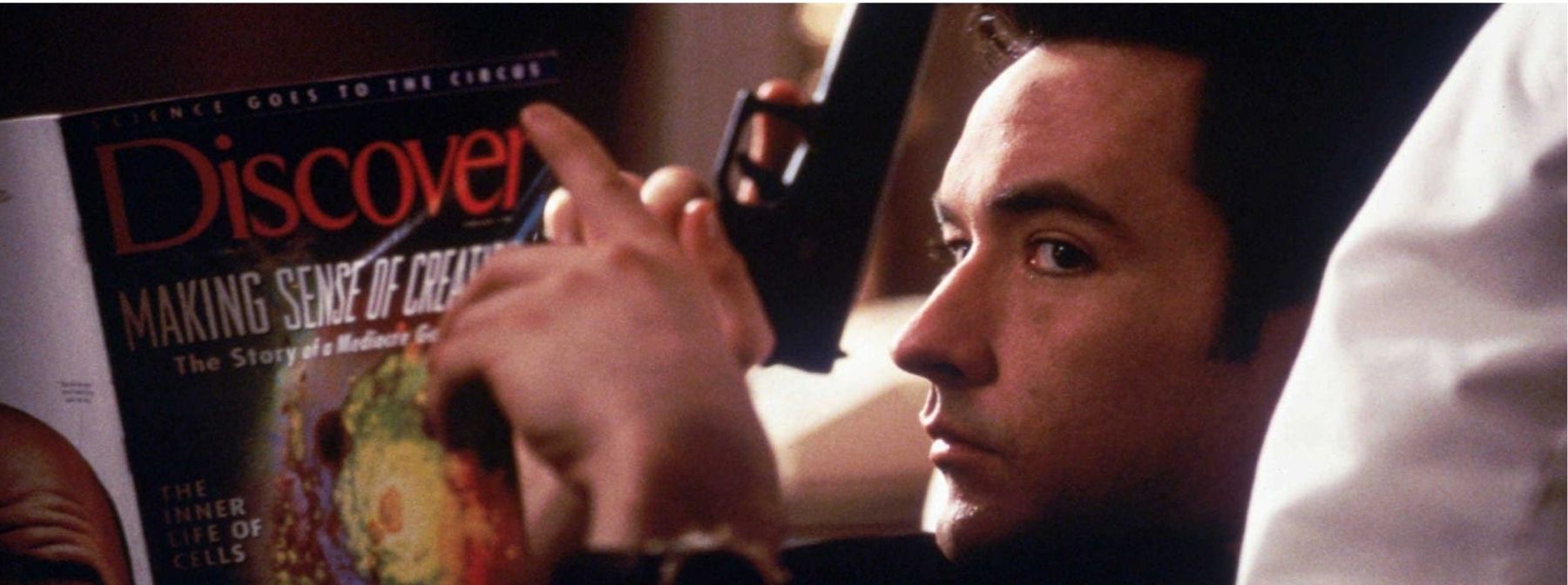

Although far from the first film to analyse the morality of murder as a career, 1997’s Grosse Pointe Blank was among the early notable titles that dared to make you sympathise with a cold-blooded killer.

Most hitmen in pop culture up to this point had something resembling a code of ethics, to ensure audiences would buy into the idea of them representing an unproblematic cool.

For instance, the titular hitman in Luc Besson’s Leon: The Professional sums up the jobs he’d take on via the simple line “no women, no kids”.

Viewers have long been trained to accept killers as protagonists, and not even particularly complicated ones, through a brief outline of their moral compasses.

Director George Armitage’s film, a modest commercial success that has since blossomed into an enduring cult favourite, resonated largely because of the way it pushed this idea of an endearing hitman to the extreme.

In the latest issue of our free digital magazine The Lowdown, we reflect on the above and how it's proved influential on the genre in the years since.

For all things pop culture, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok.

Related Articles