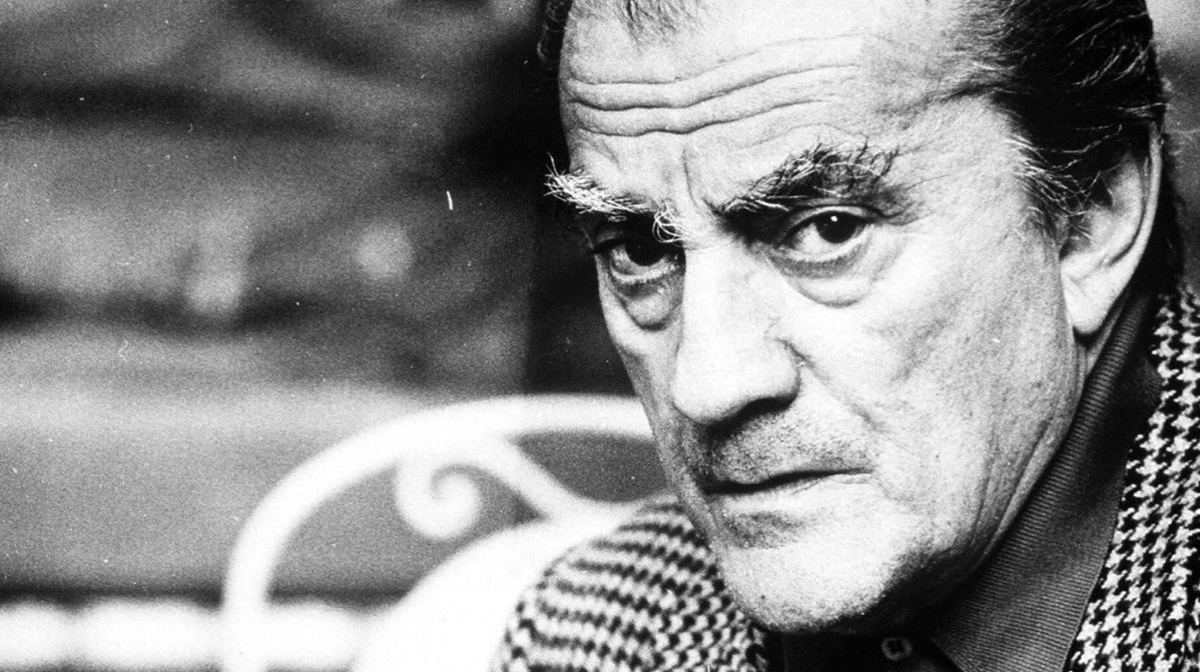

Luchino Visconti (1906-1976) was one of the founding fathers of neorealism and had a major influence on a whole new generation of filmmakers today. He delivered some of the most stylistic and sumptuous films of Italian post-war cinema that continue to resonate today within the works of directors like Wes Anderson with his vibrant colour palettes, and Francis Ford Coppola in gangster family drama The Godfather. Moreover, as an openly gay film director, Visconti can be considered as paving the way for a movement we now call queer cinema with his homoerotic classic Death in Venice.

Born in Milan into a rich, aristocratic family, Visconti grew up with a love of theatre and music. He moved to Paris in the 1930s, where he met prominent creative types such as Coco Chanel and Jean Renoir, who introduced him to the art of filmmaking. During the Second World War, he was briefly imprisoned by the German Gestapo due to his Marxist views, and life under fascist dictatorship is a theme that recurs in films like The Damned (1969).

Visconti’s film career began in the early 40s with the release of Ossessione (1943), a film that’s often considered as the predecessor of the Italian neorealist movement. Neorealism was a response to the cultural and social turmoil in Italy after the war and demonstrated a concern with the lives and conditions of individuals from the lower classes. Although Visconti was hailed as one of the first neorealists, he moved away from the city streets and the small budgets in his later career and focused more on decadency and the degradation of the upper classes with films like The Leopard and Death in Venice.

The Leopard (Il Gattopardo) (1963)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tHIsJszVBJU

Written by: Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa (author), Pasquale Festa Campanile, Enrico Medioli

Starring: Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon, Claudia Cardinale

Cinematography: Giuseppe Rotunno

“We were the leopards, the lions, those who will take our place will be jackals and sheep, and the whole lot of us- leopards, lions, jackals and sheep- will continue to think ourselves the salt of the earth” (Prince Don Fabrizio Salina).

Based on the novel by Tomasi di Lampedusa, The Leopard paints an astonishing portrait of the crumbling upper class against the backdrop of political radicalism in 19th century Sicily. Don Fabrizio Corbera (Burt Lancaster), Prince of Saline, is an ageing aristocrat whose powers are taken over by a new rising middle class. In order to save some of the old nobility’s power and wealth, the Prince arranges a marriage between his nephew Tancredi (Alain Delon) and the beautiful daughter of the new bourgeois mayor, Angelica (Claudia Cardinale).

The Leopard was described by Martin Scorsese as ‘one of the films I live by’ and won the Palme d’Or in 1964. It’s Visconti’s first major budget film (it cost about 7 million dollars to make, almost enough for production company Titanus to go bankrupt) and his second film in colour, shot on Technirama, which resulted in its sharp, high-quality images and widescreen picture. The film is highly detailed and features decadent, colourful shots of majestic buildings, violent battles and the most lavish of parties.

Lasting a solid three hours, The Leopard captures a tumultuous moment in history that reflects the prospective political changes of the 1960s. It makes up for a miraculous viewing experience with its marvellous costumes and wonderful sets and ends with a 45-minute long ball in which the younger generation of the nouveau riche is sadly but beautifully contrasted to the ageing, declining aristocracy.

Death in Venice (Morte a Venezia) (1971)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X4N8B1ggYc4

Written by: Thomas Mann (author), Luchino Visconti, Nicola Badalucco

Starring: Dirk Bogarde, Björn Andrésen, Silvana Mangano

Cinematography: Pasqualino De Santis

Death in Venice is a film adaptation of the novella by Thomas Mann and stars Dirk Bogarde as Aschenbach, a middle-aged composer who goes on holiday in Venice to overcome his writer’s block. Whilst spending his days at the beach and in the hotel lobby, he becomes infatuated with a young boy, causing him to bemoan his own loss of youth and purity. In the meantime, the city is in the grip of a deathly cholera epidemic.

Visconti’s fascination with the aesthetic reaches its climax in this breathtaking masterpiece from the seventies. Bogarde’s performance, as the pondering composer that’s desperately aspiring towards a certain purity and beauty, is one that will haunt you for a long time. This is most obvious when he visits a barber towards the end of the film and has his skin treated with cosmetics in order to appear younger – a metaphorical death mask.

Aschenbach’s terminal illness and obsession with the young Polish boy, Tadzio, Visconti’s very own David, represent the degradation of the artist in the search of perfection. When watching Tadzio playing on the beach, Aschenbach exclaims: ‘There is no impurity so impure as old age!” His struggle to retain beauty and youth takes place against the backdrop of mysterious Venice in the gloom of death. Brilliantly visualized by the observant camera and Visconti’s dreamlike sets and use of lightning, it’s one of the director’s most artistic and self-reflexive works.

Featured Image Source: Rex Features