Up to that point, the actor was best known as a sketch performer on the US series In Living Color, his biggest movie role being a supporting part in the final Dirty Harry movie, The Dead Pool.

And then, seemingly overnight, his fortunes turned around.

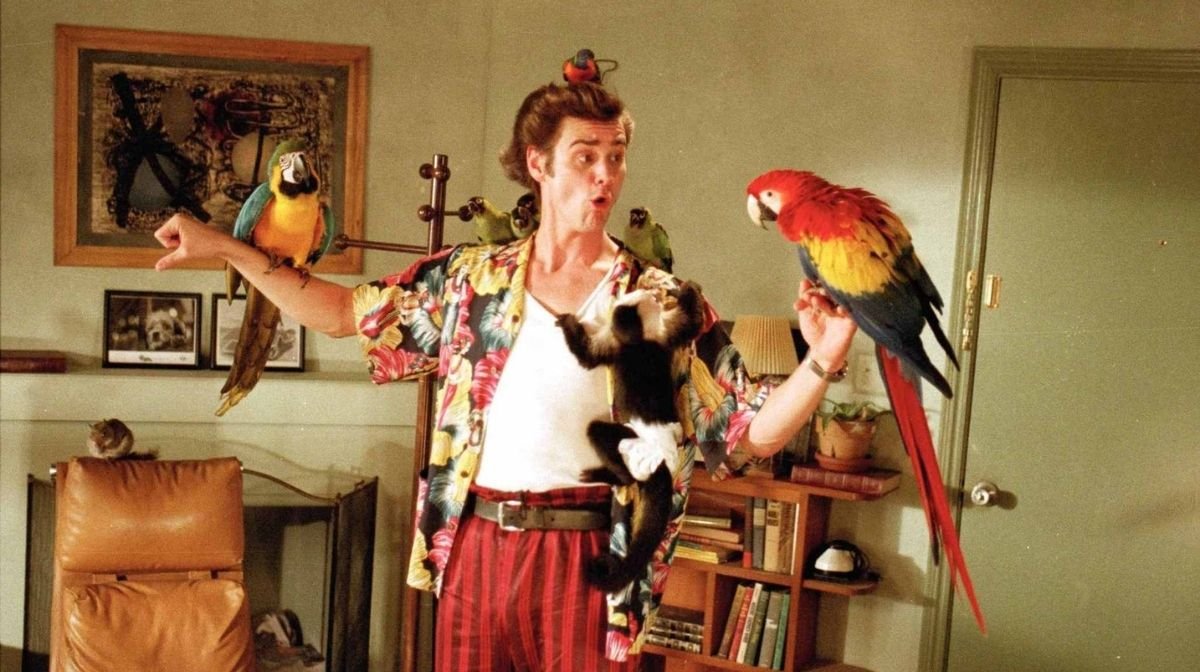

He was far from the first choice to play Ace Ventura - struggling to find any comic actor who wanted the part, producers started considering the unlikely options of Alan Rickman and Whoopi Goldberg to fill the role.

Carrey was a risk, and on top of this, he insisted he help rewrite the screenplay if brought on board, saying it needed to be more ridiculous. But the bold move paid off, helping cement Carrey's manic comedy persona, with the movie unexpectedly becoming a box office hit.

The film hasn't exactly aged well, with a string of homophobic and transphobic gags amidst the harmless toilet humour; speaking to The L.A. Times in 1994, Carrey said: "I wanted it to be the biggest, most obnoxious, homophobic reaction ever recorded. It’s so ridiculous it can’t be taken seriously".

So while the Ace Ventura films have mostly disappeared from the pop culture consciousness, they're crucial to why he became a star, with Carrey further finessing his live wire act in two movies that remain favourites to this day: The Mask and Dumb And Dumber.

That latter film, shot at the start of the year, is testament to how massive Carrey became overnight; he negotiated a whopping $7 million salary based on the success of Ace Ventura, released just before the Farrelly Brothers' movie was about to start shooting.

What's less remembered is how the public fell out of love with him as quick as they fell in love. Although now a cult classic, 1996's The Cable Guy (for which he received a record breaking $20 million payday) was a major flop, the actor being cited as the reason people stayed at home.

However, this didn't last long, with Liar Liar being billed as the big comeback - even though it arrived just a year later, in 1997.

His comedic schtick was once again top of the box office, but the film also signaled the start of a new era for Carrey, as his straightforward comedy vehicles became fewer and far between.

Seemingly aware of the minor pushback against him, he aimed to find more conventionally dramatic roles.

As one of Hollywood's biggest A-listers, it wasn't a struggle to find those projects, and the next film he made is arguably his career highlight.

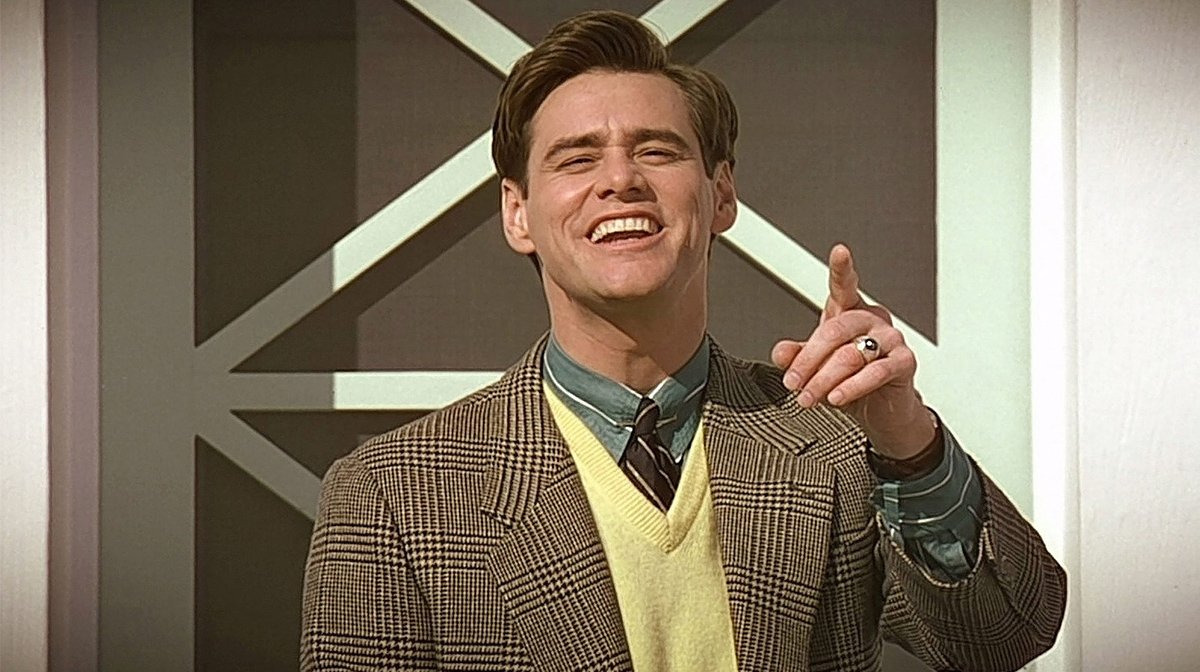

Based on how Carrey was perceived at the time, Peter Weir's The Truman Show seems like it would have been a bad fit; Carrey was best known for playing outrageous, oversized characters who would do the things polite society would never allow.

But here, he was tasked with embodying the ultimate everyman - a likeable, relatable family man that the whole world would want to tune in to see.

Yet despite how against type it may have seemed, now it's hard to imagine anybody else playing the role of Truman Burbank. The actor signed on for the project in 1995, with Weir believing nobody else would be right for the part - his bold gamble paying off in a way that recontextualised Carrey's comedic persona.

Although he would star in wacky comedies again, his character increasingly became that of the ordinary man put in extraordinary circumstances, be it becoming God or having to say "yes" to every single question asked of him.

But this shift in perception didn't happen overnight. Carrey was considered 1998's biggest Oscar snub, not receiving a nomination for The Truman Show, with the industry still viewing him as the star of lowbrow comedies, even after showing he was capable of more powerful, humane work.

It certainly didn't help that at the Golden Globes the year prior, Jack Nicholson reminded everybody of Carrey's filmography via an unexpected Ace Ventura impression in his acceptance speech, a moment still fresh on the minds of voters the next year.

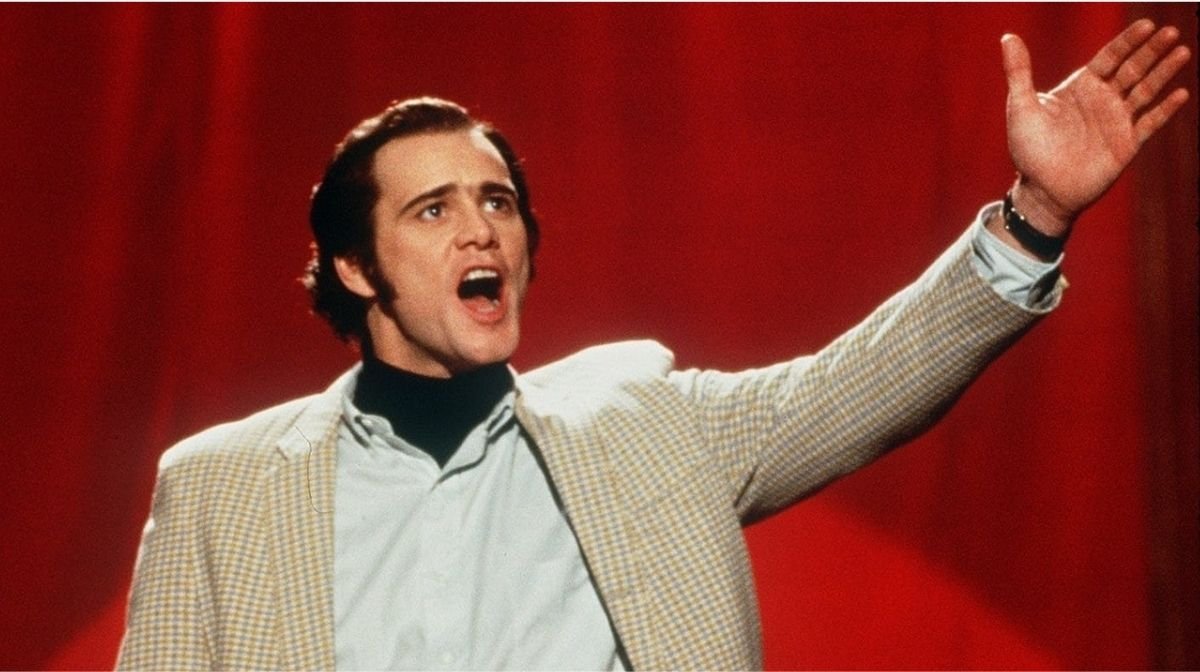

But the Globes remained the only place where his performances were getting recognised, with a Truman Show win followed a year later by one for Man On The Moon, in which the actor portrayed avant-garde comedian Andy Kaufman - a performance he infamously went fully method for, staying in character as the troublemaking entertainer for the whole shoot.

When placed together, the two performances couldn't be any more different, but both are interesting for the opposite directions they pull his persona.

Whilst Truman Show reimagines him as a comic everyman, the only aspect of normality within his world, Man On The Moon pushes his live wire act to breaking point, existing not just as a biopic of a beloved entertainer, but a meta commentary on how much that persona pushes away any aspirations of being taken seriously.

Carrey is widely considered as one of the best actors to never receive an Academy Award nomination, with his work in the 21st century going further in moving him away from that comedic comfort zone.

His performance as the awkward Joel in 2004's Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind is easily a career best, while his role as a con-man in I Love You, Phillip Morris showed that he could believably play complex gay characters, something nobody could have expected when Ace Ventura premiered.

Even the films that didn't work, such as The Number 23, or a role as a disheveled homeless man in Ana Lily Amirpour's divisive The Bad Batch, all showed a willingness to break from a persona and take roles far out of his comfort zone.

He may frequently return to comedy (and will next be seen reprising the role of Doctor Robotnik for Sonic The Hedgehog 2), but Carrey has quietly become an intriguing character actor in recent years, and deserves to be recognised for his dramatic talents as much as his comedic ones.

For all things pop culture, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.