Just about everything associated with Total Recall, which turns 30 this week, was on a grandiose scale, from the size of its budget (believed to be in the region of $65 million), to the physical stature and influence of its leading man, the one and only Arnold Schwarzenegger, who had a large hand in its making.

But it was also a movie that would have a lasting legacy. One of the last to use miniature special effects, it was also one of the first to use computer generated ones. Visual effects would never be the same again.

Not that writers Ronald Shusett and Dan O’Bannon could have foreseen that when they purchased the rights to Philip K Dick’s We Can Remember It For You Wholesale back in 1976.

The road to getting the film made was a bumpy one: over 40 versions of the script, problems in re-imagining the story as a film, and a succession of producers and directors were just the tip of a sizeable iceberg.

First in line was David Cronenberg, picking the project over The Fly but throwing in the towel after a year’s work because of “creative differences” with the producers, and returning to what turned out to be his most iconic feature.

It wasn’t until 1988 that Paul Verhoeven signed on the dotted line to helm the film we know today.

For the generations raised on the stop motion of Ray Harryhausen, Total Recall was a ground breaker, taking special effects further than anybody could have anticipated.

But it still also relied heavily on established techniques, those miniatures included. Scale model sets had to be constructed in warehouses as they were the only buildings large enough to accommodate them.

They were all used to create the Martian landscape, including the closing shot of the mutants walking out into the air (the clouds above were strung up on wires).

The spaceship was also a miniature, as was the reactor interior and the train, which takes Schwarzenegger’s character into the city and had a view of the red planet rear projected onto it, so that the passengers appeared to exit onto it.

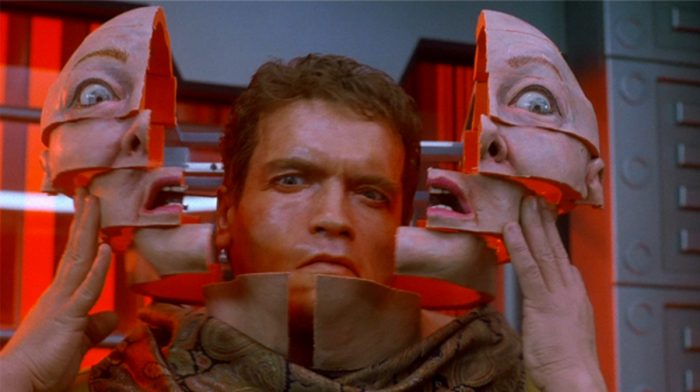

Puppets also played an extensive role in bringing the story to the screen. The bulging eyed Arnie was one, while another appeared at the very end of the scene where he removes a tracking device from his nose.

That one scene alone needed ten puppeteers. Most significantly, the Kuato puppet was built on actor Marshall Bell, who played George, a process which took up to six hours and left Bell unable to use the bathroom while it was attached to him.

Every one of Kuato’s movements was controlled by a different puppeteer, and the team totalled fifteen. All very pre- CGI.

But it was one scene in particular that marked the transition to what would quickly become the main form of special effects, effectively kicking miniatures and puppets into touch.

That came when a line of people, including Schwarzenegger’s Quaid, and – memorably – a dog all walk through the security X-ray machine.

Viewed from in front of the screen, they are shown as walking skeletons. Airport security machines hadn’t reached these levels at the time and, although medical imaging was the best real life equivalent, it was beyond the capability of movie making technology.

The special effects team were faced with the challenge of creating what appeared to be a real X-ray – with the bones looking transparent at the centre – but equally making it resemble the actors and reproduce their movements convincingly. And the only way to do this was to write special, unique software.

The mo-cap technique to capture Schwarzenegger’s own movements was a primitive version of today’s familiar tiny dots. The actor wore a body suit adorned with 18 reflective bulbs and, initially, it appeared to do the job.

But it simply wasn’t detailed enough, and the team eventually had to resort to rotoscoping the scene using other footage which included all his limbs, which enabled the skeleton’s movements to match his.

This sequence was the only CGI element in the film, and it pushed available computer technology to its absolute limit, so hand finishing was the only way to complete the scene.

There were financial pressures to contend with as well, as the budget was already tight but, to ensure that the finished version was perfect, the visual effects company put up some of their own money.

The result was something that still stands up remarkably well against today’s special effects.

It also created another piece of cinema history. In winning the Special Achievement Award for Visual Effects at the 1991 Academy Awards, it was the final live action film to receive the prize until 2018, when it went to Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu for his short, Carne Y Arena, this time for his 'virtual reality achievement'.

But, by then, CGI had completely taken over. Stop-motion had found a comfortable and, indeed, popular home in animation and, in the world of special effects, miniatures and puppets had moved from being simply old hat to obsolete.

All because of that one moment in Total Recall, one that still sticks in the memory 30 years later and which catapulted the effects industry, and filmmaking as a whole, into an entirely new world.

For all things pop culture and the latest news, follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.