Gotham's caped crusader made his initial appearance in a 1939 issue of Detective Comics (known now, of course, as DC), although many of the most famous aspects of his character had yet to be unveiled.

He still stalked the streets of Gotham late at night to catch criminals but, in line with the comic that published the strip, he was far more of a detective.

By the time Batman had outgrown these origins, he'd become a full blown superhero, regularly protecting Gotham from the supervillains who would return time and time again.

This was only heightened by how the DC universe had expanded, Batman often seen sharing panels with a one Clark Kent.

Interest in Batman tailed off over time, with DC even planning to kill him off in the early 1960s due to dwindling sales. The Golden Age Of Comics where he thrived was long since over, and people now rolled their eyes at his adventures.

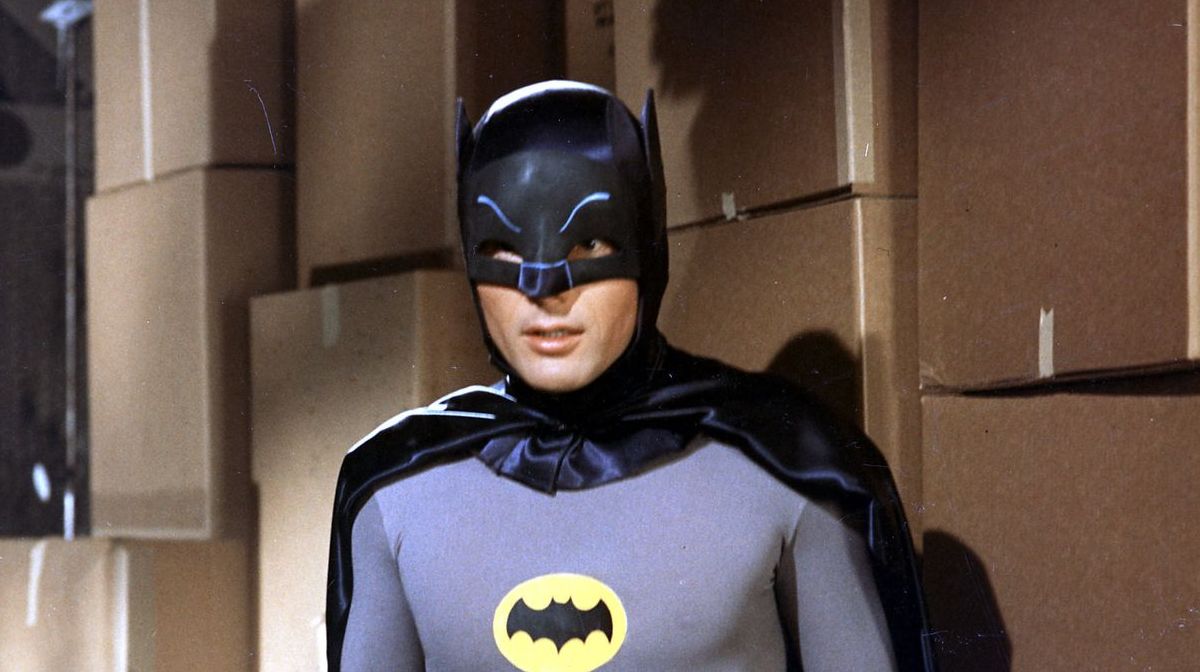

So, the franchise leaned into its ridiculousness and translated to TV as a knowing slice of camp.

The Batman series only ran between 1966 and 1968, but helped reinvigorate him in the public eye.

The show's executive producer William Dozier described the series as the only sitcom without a laugh track, and no description is more apt - to make people care about Batman again, they had to amplify his most ridiculous elements, and ensure everybody was in on the joke.

This cycle then repeated itself; twenty years later and Batman was culturally at a new low, defined by this campy theme being a world away from his roots as a hard boiled detective.

Writers of the comic book series gradually tried to move him back in that direction, but to little avail.

Instead, it took Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns, a four issue series that reimagined an aged Bruce Wayne as a grizzled detective in the Dirty Harry mode, to fully cement this vision of Batman.

Now hailed as one of the best comic book series, it has also proved to be the most influential - every new iteration of the character going forward seemed to pull some inspiration from it, but all in completely different ways.

Director Tim Burton's two Batman films (1989 and 1992) effectively bridged the gap between the ways Batman was depicted onscreen.

On the one hand, this was the most fantastical realisation of Gotham yet, the director pulling from the German expressionist films of the 1920s and 1930s in the elaborate set designs, coupling this with brilliantly over the top performances from an A-list supporting cast of villains.

But the characterisation of Batman stood in stark contrast to this. Whereas audiences previously saw him on-screen gradually becoming a parody of himself, delivering lessons of the "don't forget to eat your vegetables" variety while cracking bad jokes, this was a different figure entirely.

Burton, inspired by both Miller's series and Alan Moore's The Killing Joke, aimed to depict Bruce Wayne as a man still broken by the trauma of his childhood, his secret life as a vigilante an attempt to get closure for a crime he was too young to prevent.

In both his films as Batman, Michael Keaton can often feel like a secondary character next to the larger than life villains - a man who has disappeared so far into his suit, he can no longer find himself.

Fans were not as enthusiastic about the two Batman films that followed, in which Val Kilmer and George Clooney stepped into the iconic role, largely because they dropped the gothic and introspective aspects returning instead to the 1960s kitsch.

History repeated itself once again - audience interest dwindled, as Batman's evolution as a character went in the opposite direction, something which proved jarring considering it followed films that effectively balanced the camp with something darker.

The Burton films resonated because they were the first that directly grappled with the darker aspects of Bruce Wayne's character, a formula now frequently used when adapting comic book figures for the big screen.

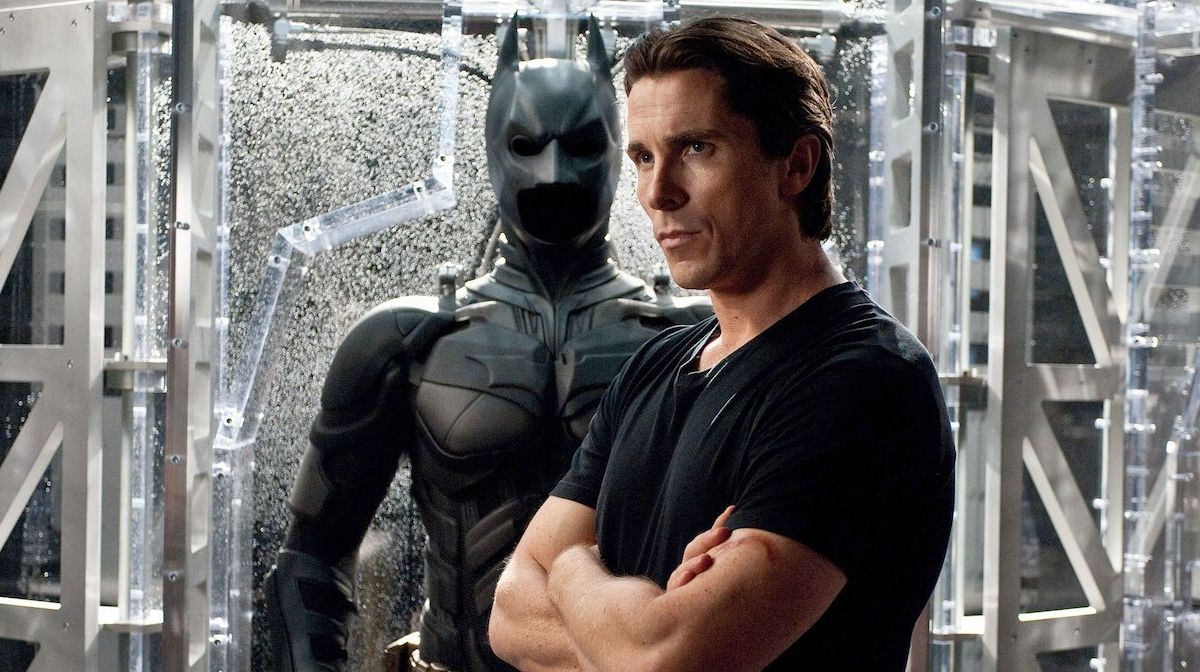

Christopher Nolan's reimagining of Gotham in his Dark Knight Trilogy, which kicked off with Batman Begins in 2005, pushed this even further still, reimagining Bruce Wayne in line with many of the anxieties of the era.

Christian Bale followed in Keaton's footsteps with his performance in the suit, but there is a clear evolution with the times in the film around him.

These are grittier Batman movies that, like many other blockbusters at the time, were inspired by the major news events of the day.

In Nolan's films, villains like The Joker are frequently referred to using the word "terrorist". Similarly, the ways in which they kill people are drawn from shocking realities, with the specter of the September 11 attacks hanging over The Dark Knight and The Dark Knight Rises as a city is reduced to rubble.

In later years, the Marvel movies may have made comic book adaptations lighter in tone - but even a film like 2012's The Avengers, with its climactic Battle Of New York, is following in The Dark Knight's footsteps, using real world iconography to ground its superhero stories.

If Bale's Batman was similar to Keaton's, haunted by his past but also to the effects of terrorism in the world around him, Ben Affleck's take on the character pushed this even further.

This was a Bruce Wayne hungry for ultra-violent revenge against criminals - a character who, upon introduction, feels more likely to shoot first and ask questions later.

His approach to fighting crime was released into a politically charged context where, through no fault of Affleck or director Zack Snyder's own, it was seen as sympathetic to right-wing grievances.

Setting aside any political reading, it feels like a logical evolution for a character who has grown ever more vengeful with each reboot.

That Batman V Superman: Dawn Of Justice was released at such a contentious moment just speaks to how the character is now enduring with every adaptation, by reflecting the widespread mood of each era.

Time will only tell how the character will be reimagined by Robert Pattinson and director Matt Reeves.

Trailers for The Batman may appear to show that Bruce Wayne is well into his emo era, but the storyline hints that the evolution may now be going full circle, returning him to his origins as a simple detective.

Batman may be the master of reinvention - but no matter how many times you reinvent yourself, you will always go back to your roots.

Click here to browse our full Batman collection.

For all the latest pop culture news and features, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and TikTok.