Even before he became a global household name on ER, he had more than a decade of TV and film bit parts under his belt - and as fun as it is now to see him randomly pop up in Murder She Wrote or The Golden Girls, it didn’t exactly signal the arrival of a major movie star, so much as a charismatic scene stealer.

When he finally got a larger movie role, in 1992’s Unbecoming Age, the film was critically reviled and almost immediately swept under the carpet, his elevation to leading man status still not clearly apparent.

Surprisingly, his first leading man role during ER’s run not only defined what kind of movie star Clooney was going to be, but also worked as a notable casting against type when placed next to his breakthrough small screen role.

In that show, the role of Douglas Ross was broadly characterised as a hero who would bend the rules wherever possible if it ensured he could save lives, his compassion often proving to be the thing that jeopardises his medical career.

But it was his second collaboration with Quentin Tarantino, who was such a big fan of ER’s first season he directed one of its later episodes, that wound up being the template for his movie star persona.

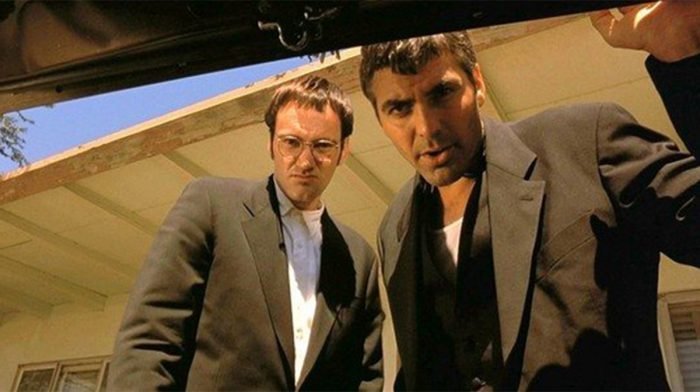

In From Dusk Till Dawn, written by Tarantino and directed by Robert Rodriguez, Clooney plays Seth Gecko, a convict broken out of prison by his mentally ill younger brother Richie (Tarantino), before resuming a crime spree following a bank robbery.

Only when placed next to the psychopathic Richie does Clooney’s character have a moral code that even has a passing resemblance to that of his TV role - and even then, it’s been sharply inverted, claiming he only kills those who deserve it, in sharp contrast to his younger sibling.

This is the darkest iteration of Clooney’s screen persona, so why is it also the one that helps define the type of characters he goes on to play?

While recently promoting his new film We Can Be Heroes, Rodriguez summarised Clooney’s appeal as that of “an everyman who can have a lot of range” from playing a hero paediatrician in one project, to a killer in the next.

Rodriguez managed to identify this in Clooney before any other filmmaker, and uses that to great effect - that everyman likability initially makes him something close to a twisted audience surrogate, our gateway into the carnage that follows.

It takes a very specific kind of movie star to be able to pull that off, and in the wake of the movie’s success, this ended up resonating with audiences more than his other big screen vehicles, bagging him an MTV Movie Award for Best Breakthrough Performance.

It was a revitalisation of his big screen career, and showed that audiences liked Clooney best when putting a darker twist on his old Hollywood-style charm.

With Clooney now cemented as a Hollywood A-lister, more conventional leading men roles in blockbusters kept coming his way - but it was his turn as Bruce Wayne in Batman And Robin that pushed him back into the zone of the everyman as anti-hero.

To this day, his involvement with that film remains a sore point; he has a reputation as a prankster, who can pull unexpected practical jokes on any cast member, and many have found that the only way they can get their own back is by mentioning Batman And Robin to him.

When Tilda Swinton won her Academy Award for Michael Clayton, she managed to embarrass her co-star in front of millions by making a gag about his Batman suit.

Clooney’s own feelings towards that film appeared to put him off starring in family friendly blockbusters altogether.

Around the same time as Batman And Robin, he ended up backing out of starring in Jack Frost (where he was replaced by another Batman, Michael Keaton), leaving the producers in an awkward situation as they opted to carry on with the original snowman they built - which in the final film still bears more than a passing resemblance to Clooney.

Out Of Sight is the film where he eases back into his charming anti-hero comfort zone, and it feels like a significantly more charming variation on Seth Gecko - another character we’re introduced to following a prison break, only to immediately re-embark on another ill planned criminal scheme.

As Clooney continued to establish this charming but untrustworthy persona, it’s notable just how many films during this period worked from this same character outline.

In his first collaboration with the Coen Brothers, 2000’s O Brother, Where Art Thou?, he leads a group of escaped convicts on a quest to retrieve buried treasure, and a year later he reteamed with director Steven Soderbergh to step into the shoes of Danny Ocean - who, once again, we’re introduced to on the way out of prison, and about to embark on his most ambitious heist yet.

Ocean’s Eleven couldn’t be further removed from his first leading role, but it’s a film that largely works because Clooney had spent so many films refining his screen persona to the point that role feels like an effortless performance only a bona fide movie star could give; making the charismatic criminal feel as much of an everyman as he does a stylised movie character.

From Dusk Till Dawn was the perfect indie vehicle for Clooney to start establishing this persona - and after a few flops following it, he realised that subverting his everyman charm was the key to remaining a big deal on the big screen.

For all things pop culture and the latest news, follow us on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok.