Director Mark Jenkin’s follow-up to his widely acclaimed 2019 cult hit Bait is a surreal, supernatural tale set off the Cornish coast that’s far harder to define than its predecessor.

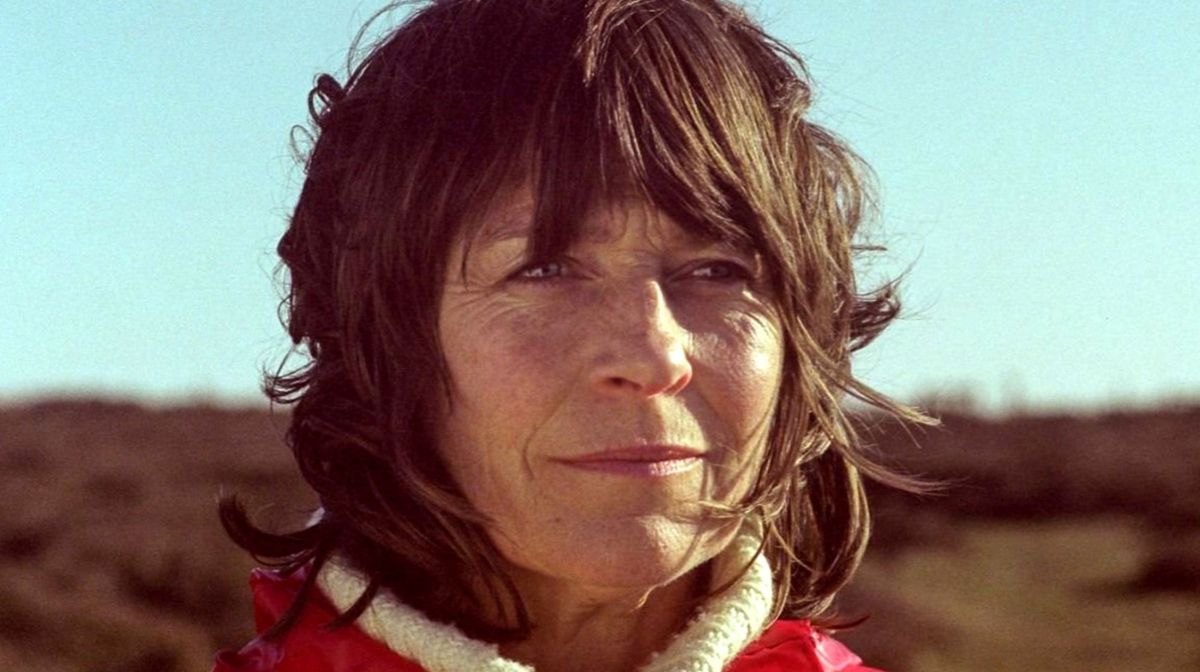

Once again shot in gorgeous 16mm, the film follows a wildlife worker (Mary Woodvine) who lives on a secluded island in 1973.

Her daily routine follows the same pattern, revolving around monitoring wildflowers on the cliff edge – but soon, her seclusion and monotony is disrupted when the flowers start growing and her grip on reality loosens.

Enys Men (which translates as “stone island” in Cornish, with Men pronounced as “mane”) is a truly one-of-a-kind experience: an unnerving oddity that you’ll find hard to shake from your system, even if you can’t fully put your finger on why.

This is partly why Jenkin is reluctant to describe his film as a horror, explaining to Zavvi: “Horror is so broad, I don’t quite know where this could sit within the genre.

"In some ways, I think of the film as a ghost story, but the sub-genre people have latched onto is folk horror, which I think is quite a distinctively English genre – even though the most famous film, The Wicker Man, is set in Scotland, folk horror is largely about the destruction of mythical merry old England.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VqSipSowkIo

"I didn’t want to make that: I set out to make a film that was Cornish, rather than English, as I feel like the Celtic Pagan perspective of folk horror is far different to the English one.

“There’s always going to be a horror element in my films because scares and thrills are what cinema is all about – but if you read the screenplay, you might think it reads more like an extended soap opera episode.

"The Guardian’s review of Bait described it as an episode of EastEnders as directed by [silent film auteur] F.W Murnau, which I’m happy with.

"The script isn’t necessarily horror, but when it comes to the film’s form, there’s a sense of foreboding that’s baked into it, which transforms it into something else entirely. Something more untrustworthy.”

Jenkin is aware that he’s made a film which is “dense and ambiguous” in contrast with his prior effort, but there are some aspects of Enys Men that don’t require intense analysis – and these are all rooted in the writer/director’s own personal superstitions.

“It sounds shallow, but the film is set in 1973 because I love the way the number looks when it’s written. I’m very superstitious about numbers, and my two lucky numbers are seven and three; it was a major coincidence that 1973 happened to be the year of The Wicker Man and Don’t Look Now, two films that have been major influences on me.

“A lot of people who grew up in fishing communities around the Cornish coast are crippled by superstition and that factors into my filmmaking. I must shoot all my films in 21 days, as that’s a lucky number for me – and my other lucky number is 53, so we’d need a massive jump in budget if we missed that deadline.

"I always cook a meal for the cast and crew the night before shooting which has gotten a lot harder as the projects have gotten bigger, and then every day at the start of the shoot, I burn Monopoly money next to the camera. I don’t even remember where that tradition even came from.”

However, Jenkin’s own superstitious mindset does feed into the historical backdrop, as the crew of a fictitious 19th century shipwreck become spectral presences as the story continues. As he explained: “People who spend their life at sea create superstitions to convince themselves they’ve got control over a situation – which, when you’re going out to sea and the chances of returning are sometimes 50/50, is the only way to block out that fear and feel like you had power over your destiny.

"It’s not a life-or-death situation, but when you’re making films, things can go wrong: you can often feel like you only have control over the production if you’re burning money next to the camera!”

The director has previously stated that trying to work out the chronology of Enys Men would likely make any audience member go mad, so the challenge for his regular collaborator Woodvine was to find some grounding within the ambiguous horrors that unfold over an increasingly fractured timeline. Jenkin refuses to add adjectives or adverbs within his script so as to not assign feelings to characters, only describing the specific images viewers will see – which he hopes will help his actors create something even more mysterious than what’s already on the page.

“I never talk about backstory – Mary can ask me about it, but I won’t always answer her questions. I will say that I’m introverted where she’s extroverted, and as every character I write is rooted in myself in some way, she brings her extrovert nature to my introvert characters which makes them harder to read.

“As she’s a trained theatre actress, she’s used to communicating subtext and emotion physically – but if theatre is about wide shots, my films are about big close ups and I don’t want those same big gestures with hands or facial expressions. Everything must be conveyed through the smallest of looks.

"I like to have signs up on set reminding everybody the camera is like a magnifying glass: the most subtle movements grow bigger when they’re registered through it”.

As with Bait, Jenkin shot Enys Men as a silent film, only post-synching the soundtrack later in the edit; it’s become one of his striking stylistic trademarks, even if it is largely a method of getting around the restrictions of working on a low budget, when a large chunk of post-production is dedicated to fixing sound recorded on location. As he describes it; “silence is my starting point – it's the white of the canvas before the painter starts doing his job”.

However, the director was preparing to completely transform the way he works for his yet-to-be-announced next project, which will have a much higher budget.

“My initial thought was that when I had a bigger crew and bigger set pieces to shoot, I’d have to film in a more conventional way; recording sound on location, working with a Director of Photography, all that stuff.

"But when I mentioned this to the team working on that project, they didn’t want to abandon the way I worked, as that’s why they were excited to develop the film with me. It will be a case of modifying the way I work to fit in with a larger scale, rather than changing anything about it.

“I think, when it comes to filmmaking, form and content should have the same amount of agency; if you ignore the form, you might as well be sitting around the fireplace and verbally telling a story. Form is what makes cinema special, and that’s why I make films the way I do – connecting with the form is as important as connecting with the script.

"I’ve been criticised in the past for being style over substance, but I think that’s an unfair criticism; style should never outweigh content, but my films are as much about the form as they are the story themselves, and I’m not ashamed of that”.

But while his next project may be his largest scale production to date, don’t expect Jenkin to make the transition to directing blockbusters any time soon.

“Those movies just don’t play to my strengths as a filmmaker”, he concluded. “I’d be the guy who got booted off the project at lunchtime on the first day of shooting.

“And besides, if I did direct a Marvel movie, I can promise you one thing: it would be the S******t Marvel movie you would ever see”.

Enys Men is released in UK cinemas on Friday 13th January.

For all things pop culture, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok.