The final year of the 20th century was one of best for movies since movies were invented. But even among the five-star likes of The Matrix, Magnolia, The Sixth Sense and Being John Malkovich, one film stands out.

Or at least aside, smirking knowingly at the others from behind a pair of red-tinted sunglasses, with a cigarette poking out the side of its mouth. It was so bold, so crazy, so inventive, so challenging, so like nothing we’d seen before.

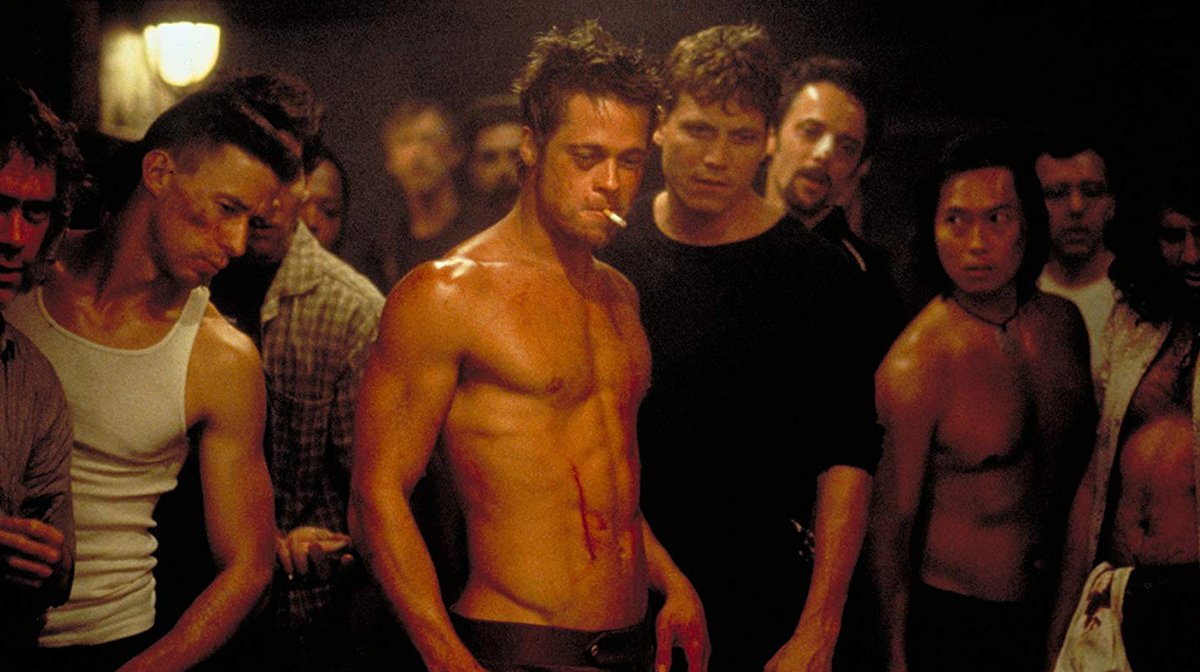

No doubt about it, Fight Club packed a punch. It remains a blood-flecked masterpiece. And it totally bombed at the box office.

Of course, that’s not unusual for a great cult movie. Blade Runner, one of the most influential sci-fis ever made, was also a flop. But Fight Club’s commercial fate (during its theatrical run, at least) feels particularly appropriate to its sly, subversive, self-harming heart.

20th Century Fox

Put together on a big studio budget ($63 million) and starring big names (Brad Pitt, Edward Norton, Helena Bonham-Carter), it looked from the outside like a slick action thriller about a young man (Norton’s unnamed narrator) drawn into a seedy, dangerous world of underground, bare-knuckle punch-ups.

The truth was, its studio, 20th Century Fox, was terrified and confused by the film. They didn’t know what to do with it.

This was partly because its slick, big-budget packaging contained an explosive anti-consumerist message, aimed as much at companies like Fox as any other.

It was also partly down to the fact that it mischievously pushed taste boundaries, with its blipvert insertions of pornographic images, a sense of humour so dark it wrung laughs out of terminal-illness support groups, and contained lines like, ‘I haven’t been fucked like that since grade school’ (yikes).

20th Century Fox

But the other thing about Fight Club is it was so hard to pin down.

It was so packed with concepts, so overflowing with style, it felt like it didn’t belong in any single genre. Fox didn’t know how to sell that.

And that’s what makes it so awesome. Fight Club is a movie that simultaneously exists within several different genres. It is, in a sense, a film for everybody, depending on your point of view…

It’s A Coming Of Age Movie

20th Century Fox

When director David Fincher first read Chuck Palahniuk’s novel Fight Club he instantly saw that his film could be an ‘heir’ to, of all things, 1967’s coming-of-age classic The Graduate. So much so, that he sent the book to Graduate screenwriter Buck Henry to gauge his interest (Henry didn’t get it).

That film’s main character Benjamin Braddock (Dustin Hoffman) was an aimless youth, uninterested in following the paths laid out for him by the older generation. Fight Club’s narrator enters the story just as existentially misplaced, albeit in the form of a 30-something Generation X-er who realises that post-war values which push consumer-based comfort and ‘security’ leave him feeling profoundly empty.

On his journey to figuring things out, Benjamin does something shocking: he sleeps with a much older, married woman. Fight Club’s narrator, meanwhile, forms a paramilitary anarchist organisation.

And where The Graduate ends with a young man and woman, side by side on a bus, unsure of their future together, Fight Club ends with a man and woman holding hands while watching several buildings explode and collapse. ‘You met me at a very strange time in my life,’ the Narrator tells Marla (Bonham-Carter). A time which he has, in his own screwed-up way, finally grown out of.

It’s A Psycho-Thriller

20th Century Fox

To be fair, this is what you would have most expected from the director of Seven and The Game. Fincher has always seemed more comfortable with the uncomfortable, taking us to dark, difficult places where things are not always as they seem.

Before M. Night Shyamalan became lauded as the late-’90s master of the big, gobsmacking plot twist, Fincher had already delivered a pair of doozies in his previous two films, having Seven’s mysterious serial killer turn himself in halfway through the film (then delivering a rather famous head in a box), and giving seemingly brooding thriller The Game a surprise happy ending.

Fight Club had the best Fincher twist yet, one rooted in the fact that we only see the film’s events through the eyes of Norton’s character, who is suffering from insomnia (which in turn triggers another mind-sundering psychological condition) and therefore can’t be trusted.

He is, quite literally, his own worst enemy.

It’s A Romantic Comedy

20th Century Fox

If you took the grubby, derelict-house surroundings and replaced them with a white-and-beige backdrop, some scenes in Fight Club could have come right out of a Nancy Meyers movie.

Like the almost French-farcical swinging-bedroom-doors interactions between Tyler (Pitt), Marla and the Narrator. Or the zingy hate/love banter between Norton and Bonham- Carter. There’s even a ‘race for the girl’ climax, although it does admittedly also involve a van full of explosives.

Funnily enough, Fight Club’s screenwriter Jim Uhls told Salon.com that he saw his script as a ‘romantic comedy, but not a typical romantic comedy’ — in that it had to do with ‘the characters’ attitudes towards a healthy relationship, which is a lot of behaviour which seems unhealthy and harsh to each other, but in fact does work for them. Makes perfect sense.

It’s A Superhero Movie

20th Century Fox

Like most modern superhero films, Fight Club is bombastic, spectacular and packed with cutting-edge visual-effects shots. The final scene, in which we see those buildings so artfully collapsing, took a year of painstaking work to create using CGI.

But it’s also a story about a person finding a power within themselves — a power which manifests as an alternative identity. Bruce Wayne wanted to bring justice to the streets of Gotham and became Batman. Bruce Banner (who, perhaps not entirely coincidentally was later played by Edward Norton) couldn’t control his rage and became the Incredible Hulk.

Fight Club’s narrator wanted to escape his desk-cubicled, IKEA-furnished life and became Tyler Durden.

20th Century Fox

In this sense, Fight Club is very close to 1999’s other kinda-superhero movie, The Matrix, where Thomas Anderson (Keanu Reeves) literally escaped his soul-crushing reality and transformed into the can-do-anything Neo.

Although Tyler Durden is not literally superpowered, just empowered by his dismissal of social norms — even though that develops into recklessness and ultimately a callous disregard for human life.

It’s like Harvey Dent would say nine years later in The Dark Knight: ‘You either die a hero, or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.’

It’s A Satire

20th Century Fox

Another movie which has parallels to Fight Club is one of cinema’s darkest comedies: Dr Strangelove, or How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

In the latter, Stanley Kubrick turned nuclear armageddon into a joke — which turned out to be a great way to tackle the insanity of global mutually assured destruction, although at the time, many who saw the film found it offensive, not least thanks to its bleakly explosive ending.

Fight Club makes comedy (and explosions) of something a little less easy to pin down than nuclear war. That’s because its satire aims wider, taking in consumerism, therapy, male toxicity and fascism.

As with Strangelove, many critics missed the point and took umbridge. The Evening Standard’s Alexander Walker described it as ‘an inadmissible assault on personal decency, and on society itself,’ going as far as to say, ‘it resurrects the Führer principle.’

20th Century Fox

Absolutely, Fight Club portrays disaffected men — who see themselves as the ‘middle children of history’ — grouping together and mobilising in a reprehensible way. But their actions are hardly celebrated, or even excused.

Come the conclusion, Fight Club’s morality is clear: Tyler has gone too far, he’s a psychopath and he must be stopped.

The joke is clear, too: it’s simply ridiculous that all these men are so willingly follow this troubled individual — someone who doesn’t even agree with himself. They don’t see or hear what’s really there, only what they want to see or hear.

A message no less relevant 20 years later, in this era of incels, populism and the so-called alt-right, than it was on its release.