A wise man said, “once you overcome the one‐inch‐tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films”.

So, you want to expand your palate? Great, but it can be slightly daunting. One must ease into foreign language films, gently not aggressively.

You have to understand yourself before understanding foreign features. What do you like? What do you respond to? What are your shortcomings? You’re not going to adore everything, so why not start in comfort and familiarity?

With that in mind, we have collated a list of like‐minded foreign language films with inflections, motifs, or direction that one might already be accustomed to. Read, watch, enjoy! You might find a new favourite!

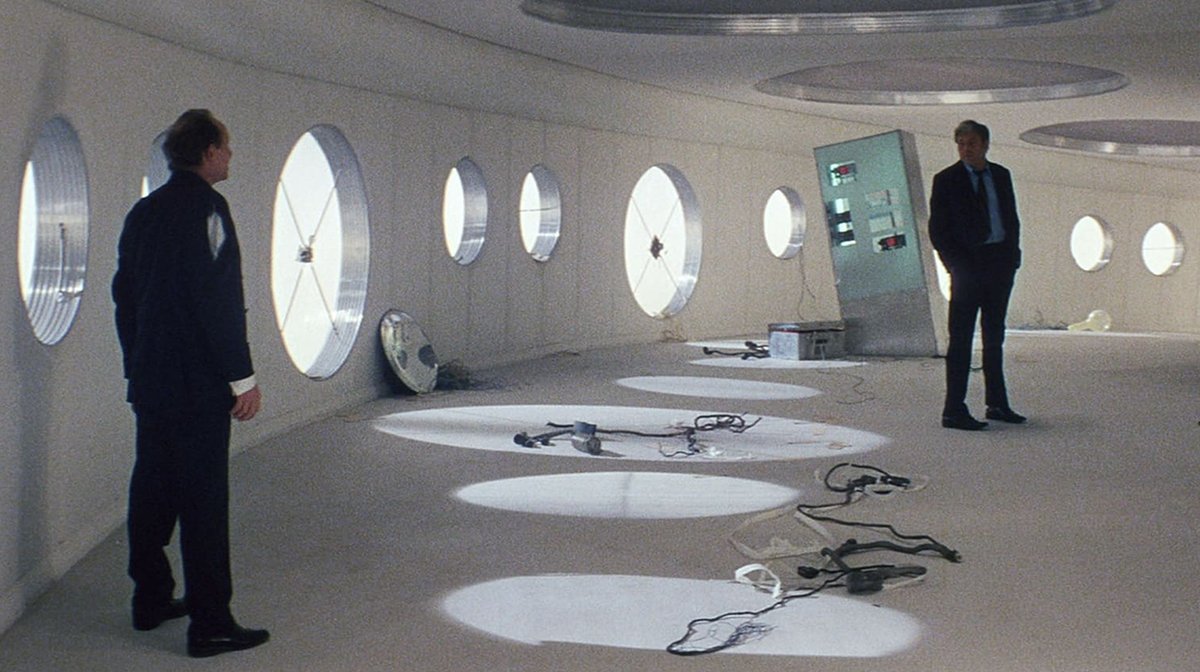

Loved 2001: A Space Odyssey? Watch Solaris.

Mosfilm

The philosophical and trivial nature of 2001: A Space Odyssey utilises the extreme heights of science-fiction to question our present realities. Kubrick’s legendary feature is a firm favourite amongst film fans, flaunting its ground‐breaking visual effects, confirming its position within the film canon and as a pioneer of the genre.

Enter Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris. The film was originally marketed as “the Russian answer to 2001”, much to Kubrick’s amusement, being visually and thematically similar.

Arguably, the existential nature of both films solidify why they are so loved, outreaching ideologies of human life and mental observations, alongside furthering boundaries of the filmmaking process.

But, wide‐eyed speculation aside, both are narratives engulfed in wonder; an equally reflective and transformative experience best paired wearing a dressing‐gown with a gin and tonic in hand.

Loved Zodiac? Watch Memories Of Murder.

CJ Entertainment

Before Parasite, there was Memories Of Murder, Bong Joon‐ho and Song Kang‐ho’s first collaboration.

Similarly to Zodiac, both true‐to‐life depictions are bleak and obsessive but deeply engaging, arguably awakening the inner detective.

The infamous Zodiac Killer story echoes through our westernised households, so audiences should expect parallel levels of notoriety in South Korea. Both thrillers should feature synonymously in the serial killer canon.

Loved Stand By Me? Watch I Wish.

Gaga

Stand By Me forever evokes a fondness of youth; a constant reminder of a nostalgic camaraderie, albeit missing a dead body.

Hirokazu Kore-eda, of Shoplifters fame, directed, wrote, and edited I Wish, a story about two brothers withdrawn and separated, both living with a solemn parent.

Deeply missing each other, the boys hear a rumour that when two trains pass on the almost completed Kyushu line, a miracle will be granted, so they hatch a plan to reunite their family.

With equal naivety and charm as the children in Stand By Me, the story is a harbinger of darker undertones; I Wish especially, and eloquently, establishing complex relationships with an air of melancholy held together by the brothers’ warmth.

Loved Black Swan? Watch Perfect Blue.

Rex Entertainment

An artist’s obsession has been detailed more times than a Swan Lake needle drop. Black Swan blurs the boundaries between life and imagination, a descent into the cavities of the mind and perhaps a conversation about schizophrenia.

Perfect Blue pins yourself as your worst enemy unable to determine your own identity. Mima Kirigoe, the lead, confuses personal delusions that mirror external characters, much like Natalie Portman’s Nina identifying as a martyr.

Some label Socrates as the ultimate questioner, but he never saw Perfect Blue.

Loved Forrest Gump? Watch Cinema Paradiso.

Miramax Films

Whilst dissimilar in content but more so in structure, Forrest Gump and Cinema Paradiso share an episodic format and narration style – a guide, if you will, to navigate the filmic landscape.

Both are meditative reflections on the past, sentimental but never mushy, a slideshow of classic ‘moments that made me’, equally positive and negative.

Cinema Paradiso is more subdued than Forrest Gump, but a celebratory vignette on life. And the movies.

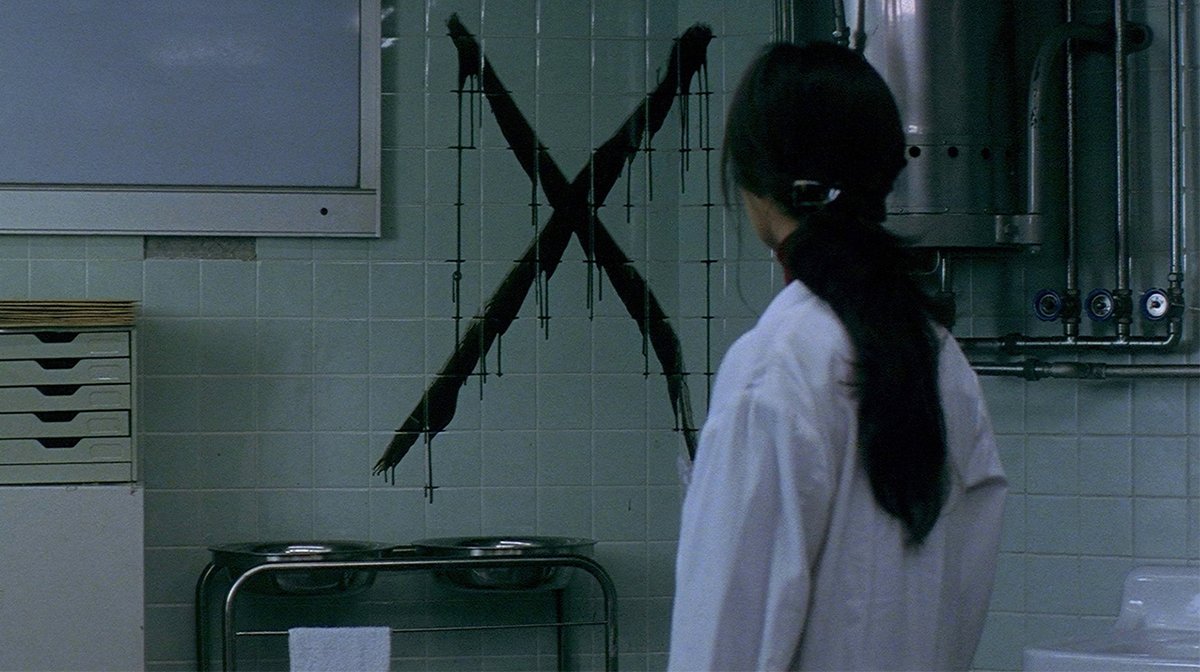

Loved Se7en? Watch Cure.

Daiei Film

Alike Zodiac and Memories Of Murder, Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Cure also takes a podium position in the serial killer oeuvre.

Yet, the fictitious Cure replicates the narrative beats of David Fincher’s Se7en more than the above‐mentioned thrillers.

Persistent terror propels hysteria, transporting the audience to a foggy noir underworld. These rumblings keep the tension spiky; if you let your guard down you might become entwined.

And no, he’s not Akira Kurosawa’s son.

Loved Mr Bean? Watch Playtime.

Les Films de Mon Oncle

The clumsy but ebullient Mr Bean found his origins in Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot, a recurring personage in his directed pictures.

Whilst the Tati anthology took a while to find its footing (much like Hulot himself), Playtime is his magnum opus, a clear culmination point for his work.

It is a cascading metanarrative and an obtuse observation on French cinema and the film industry, yet there is no construed pathway, the plot is as chaotic and bumbling as the lead.

But, plenty of pizzazz and much craftsmanship signifies Hulot’s outing as a work of genius.

Loved Over The Hedge? Watch Pom Poko.

Studio Ghibli

There’s more of a connection than raccoons, I promise. Surprisingly, both Over The Hedge and Pom Poko showcase ecological imbalance, modernisation through suburban deforestation, and the transformative power of testicles – actually, that’s just Pom Poko.

Nonetheless, both animations centralise the diminishing disregard humans have for wildlife by positioning an empathetic audience alongside the animals.

Unlike the tell‐tale iconography of Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata succinctly blends wider contextual issues and traditional Japanese folklore with childlike whimsy, in true Studio Ghibli style.

And, like the best Studio Ghibli features, urges the viewer to reflect on themselves.