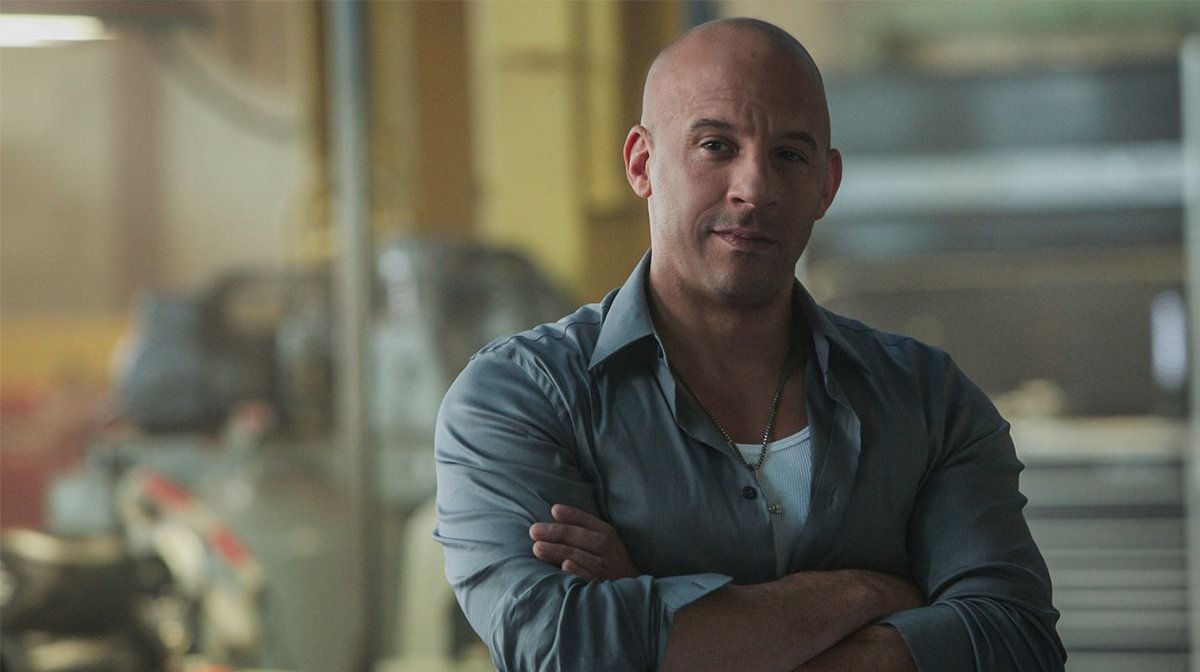

These days, when we think of Bruce Willis, one of two things comes to mind.

The first is the image of the wisecracking action hero immortalised in Die Hard, who captured the attention of audiences around the world as an everyman pushed into extraordinary circumstances.

The second image is that of the current Bruce Willis, more often than not sleepwalking through a straight-to-video action film, a shadow of his former self, drained of all the charisma that was once so effortless.

Universal Pictures

What is often overlooked is his power as an actor outside of the genre for which he is most famous, quietly turning in career best work in everything from stripped down M. Night Shyamalan thrillers, to offbeat Wes Anderson comedies.

Willis has been cast against type to thrilling effect many times before, but his finest performance of all was initially undervalued for just how much it subverted his stereotypical screen persona.

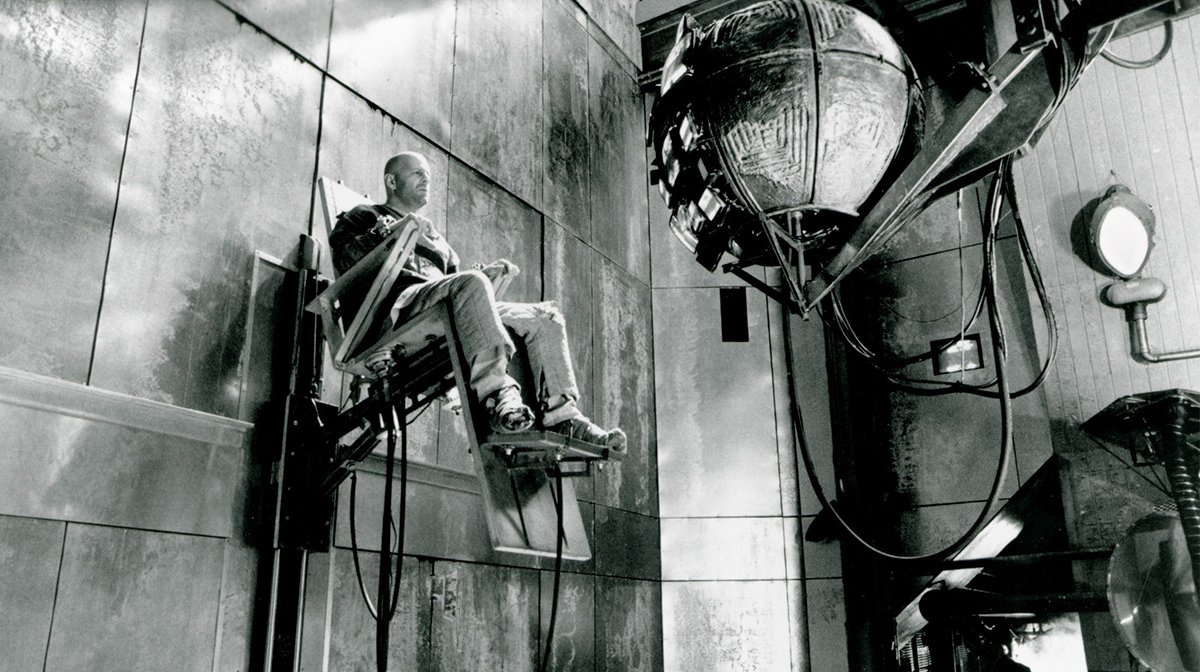

As the lead in Terry Gilliam’s time travel-meets-pandemic paranoia thriller 12 Monkeys, Willis was very knowingly cast in a role that’s very much the polar opposite of John McClane.

Rather than the everyman hero who singlehandedly foils a terrorist plot, here was an everyman anti-hero thrown back in time, powerless to stop the chain of events that leads to humanity’s near extinction.

Universal Pictures

Largely because of an awareness to how much audiences viewed Willis’ persona in tandem with the John McClane character, Gilliam was initially reluctant to cast Willis as James Cole – his first casting choice was Nick Nolte, a decision Universal Pictures objected to.

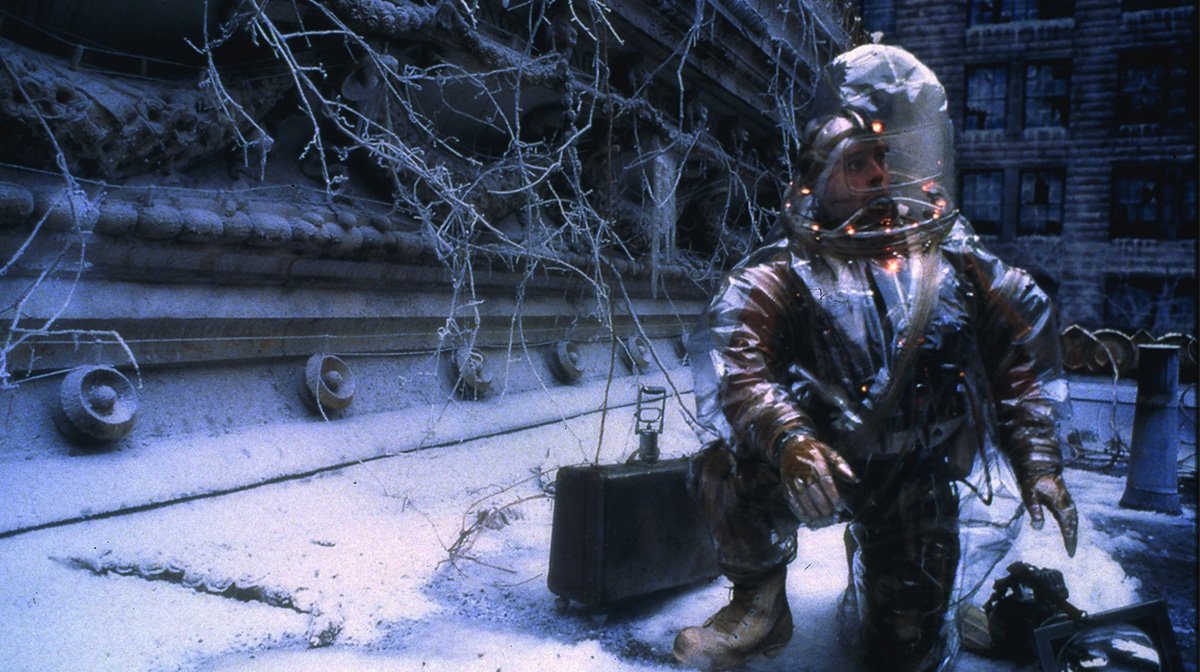

Naturally, as a studio willingly financing a big budget adaptation of the short, experimental sci-fi La Jetée, they needed someone with the A-list capital to get bums in seats.

Similarly, the studio also rejected his choice of Jeff Bridges as Jeffrey Goines (who would eventually be played by Brad Pitt), but it was through Bridges that Gilliam first met Willis years earlier, during the casting process of his previous film The Fisher King.

20th Century Fox

Gilliam changed his mind on Willis after watching Die Hard, where one scene in particular stood out for him: a moment where McClane talks about his wife while picking out shards of broken glass from his foot.

In the midst of the chaos unfolding in the Nakatomi Plaza, this was more than enough to convince the director that Willis had the appropriate tenderness needed for the role.

But unfortunately for Willis, Gilliam had a long list of exacting demands he would need to meet to give the performance the director wanted from him.

Universal Pictures

And by “exacting demands”, I mean Gilliam went through most of Willis’ filmography to write up a list of recognisable tics and quirks he’d seen the actor do in multiple performances, and forced Willis to go against all instincts to sink into the role.

The director’s perfectionist streak ensured it was a nightmare shoot for the whole cast, at one point endlessly reshooting a sequence featuring a naked Willis, all because a hamster in the background of the frame wasn’t running round in its wheel like it was supposed to.

This incident became the most notorious of the entire shoot, and even coined the name of the film’s making of documentary: The Hamster Factor.

Universal Pictures

It all paid off, with 12 Monkeys becoming the biggest commercial hit of Gilliam’s career, spending two weeks at the top of the US box office and going on to gross more than $160 million worldwide.

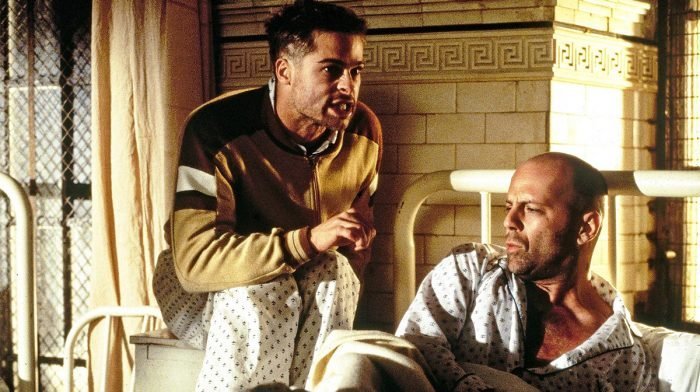

But at the time, Willis’ performance remained largely undervalued, with all eyes on Brad Pitt’s deliriously hyperactive supporting turn, which earned the A-lister a Golden Globe alongside his first Oscar nomination.

And while Pitt’s bug eyed madness is what commands attention on first viewing, repeat watches reveal that Willis never had the show stolen from him by his younger co-star.

Universal Pictures

When working with perfectionist directors who demand multiple takes, many actors’ performances can become robotic in the process – fine tuned to the wishes of their boss, but lacking a recognisable humanism.

This is why Willis’ performance in 12 Monkeys is the strongest in his filmography; forced to be stripped of his movie star persona, he becomes a recognisably flawed person, thrown back in time and finding himself powerless in a world that can’t possibly understand him.

When placed next to Pitt in the first act, set almost entirely at a Baltimore mental hospital, it’s easy to see why you’d overlook Willis.

Every Gilliam film has an oversized cartoonish performance (his following film, 1998’s Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas, would be comprised entirely of them), and with his comedy background, it’s obvious that the director is drawn to them.

Universal Pictures

But the reason Pitt’s performance is so effective is because of how Willis manages to ground the madness.

After all, he became a movie star convincing audiences that an everyman could be an action hero, and for his career best work, did the exact opposite: convincing them that a classic action hero could crumble and become a flawed everyman once again, all in the midst of the most high concept film he’d ever star in.

For all things pop culture and the latest news, follow us on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok.