There was nothing like going to the video store. You could peruse the aisles at your leisure, and ogle at each of the terrifying covers in the horror section.

The bright colours and strange imagery would catch your eye, and you’ll never forget the fear generated from that one image.

But what if you found out that, on top of the shocking artwork, the film was also banned in several countries due to its depravity?

If you’re like me, that’d make you even more interested in the film. That was what happened with Britain’s video nasties phenomenon of the 1980s.

Kaleidoscope Home Entertainment

The term ‘video nasty’ entered public consciousness in 1982 as the VHS market was ramping up in the UK. Home entertainment became widely popular and access to horror movies, among others, was given to children.

This meant lower budget exploitation horror films could earn more recognition at the local video store rather than fighting for cinema showings.

But, concern grew over just how accessible these films were, and how they were corrupting the minds of Britain’s youth.

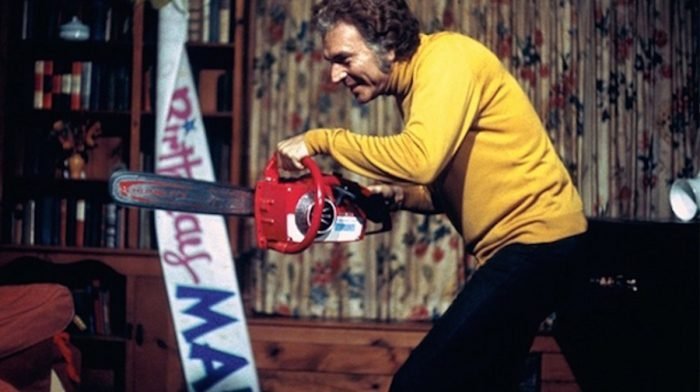

Massive adverts for films like The Driller Killer showed off a world of depravity and violence. Such images began to rile up the public, with the press deeming such films as video nasties.

Rochelle Films

But what was to be done about this? Well, censorship of course.

At first, the authorities used the Obscene Publications Act of 1959 to prosecute 72 films for their depictions of gore, violence, rape, cannibalism, and more.

These 72 films were the original video nasties, which were each reviewed and sometimes prosecuted for their content. This included I Spit On Your Grave, The Last House On the Left, Cannibal Holocaust, and The Burning.

Filmways Pictures

Just because those films were declared by some as repulsive, it didn’t deter others from seeking them out. In fact, just the idea of a list of banned films only made them more interesting.

Video nasties brought exploitation cinema to the forefront of people’s minds, fascinating them with descriptions of bodily decay, sexual violence, and animal cruelty.

It’s like when you’re told not to do something — you only want to do it more. Thus began the cult following and desperate attempts to gain access to these films, which would then inspire future filmmakers.

Hallmark Releasing

To avoid the repeated proliferation of video nasties and to curb the enthusiasm for sleaze, the Video Recordings Act of 1984 declared that all films released to video had to be reviewed by the British Board Of Film Classifications (BBFC) to make sure they were appropriate for public consumption.

And no film was grandfathered in. Every film previously released had to be re-submitted for review.

This effectively paved the way for censorship of whatever the authorities deemed inappropriate for children. A member of the BBFC explicitly stated:

“Audiences in Britain never see the worst the world’s filmmakers have to offer… such things are habitually cut or rejected in British cinema. If

were permitted, I believe the public would demand that the police and the courts and Parliament take a far tougher line with cinema than they have so far.”

Nuova Linea Cinematografica

There was pride taken in this system of control, seeing it as a way to maintain morality rather than expose children to sex and violence.

In total, 39 films were prosecuted and subsequently banned or subjected to heavy editing until later review decades later, including horror classics directed by Wes Craven, Abel Ferrara, Lucio Fulci, and Dario Argento.

Others that were not prosecuted were dropped from the list of video nasties, but were still subjected to heavy editing if they wanted a release.

Metro-Film

The arbitrary selection of films can be seen in The Witch Who Came From The Sea’s classification as a video nasty.

It was included due to its tagline, “a young woman’s nightmares of incest and castration” when it is more of a psychological horror film.

These movies were quite literally judged by their covers, and were quickly subjected to censorship without any research.

MCI

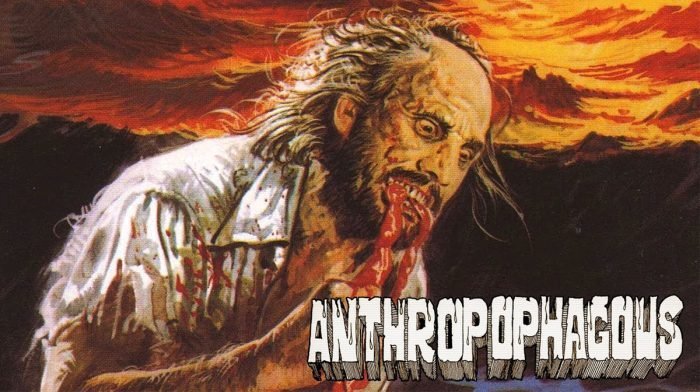

Then there were the decades of editing and petitioning for re-release for films such as Antropophagus. The 1980 cannibal film is considered one of the most infamous entries on the list.

While initially released uncut, it was eventually prosecuted and removed from distribution in the UK. It wasn’t until 2015, 35 years later, that Anthropophagus finally got an uncut release at all.

Also while the term ‘video nasty’ was specifically used in the UK, the label spread internationally and affected subsequent judgments abroad. And yet, as stated in the book Cult Cinema: An Introduction, this only aided in Antropophagus’ cult following.

Cinedaf

While subsequent laws have removed such strict limitations of what can and can’t be viewed, or distributed in the UK, cinematic censorship does continue today with video nasties.

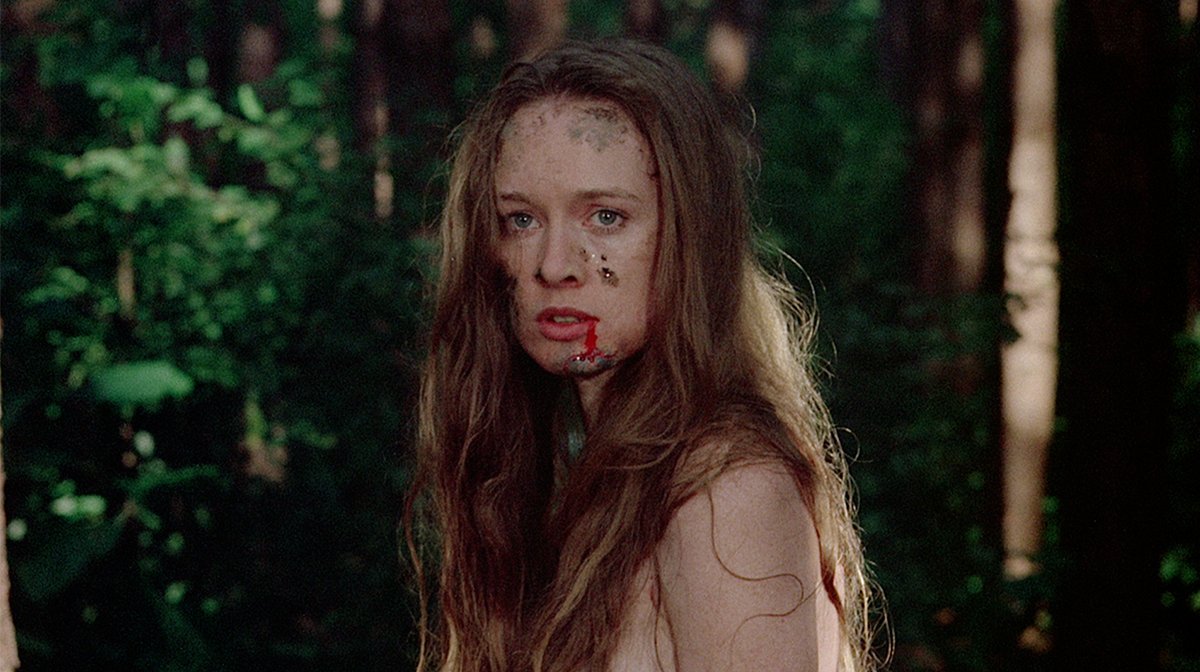

One of the biggest examples is the rape-revenge film I Spit On Your Grave. Despite recent releases in the 2000’s, parts of the film are still cut in Britain to keep it at an 18 rating.

A total of three minutes have been edited out to make sure it complies with the ratings board. This is also the case with Cannibal Holocaust that still had to cut 15 seconds of its runtime to achieve a new release.

So despite new laws and ideas of creative expression expanding, arbitrary rules still declare what is and isn’t good for the public to consume.

United Artists Europa

But this isn’t just the case with video nasties and exploitation cinema. Rating systems in general create limitations on what can be shown or said.

Ratings often dictate who comes to see a film too, so if a movie can’t get a low enough rating, their financial hopes only drop.

Films are then edited down to fit the guidelines, made into something declared palatable by the system.

Kaleidoscope Home Entertainment

Despite these attempts of control, exploitation films have persevered and even flourished with such a reputation. The term ‘video nasty’ was supposed to be a deterrent, but actually more people wanted to see them.

It became a marketing tool that only bolstered the films’ reputations not only in the UK, but around the world.

Rules and regulations couldn’t stop directors from their ideas of creative expression, and that still remains true.

If the era of video nasties can teach us anything, it’s that despite its best efforts, the cycle of control cannot defeat the passion of the artist.