By Frazer MacDonald / @frazermac44

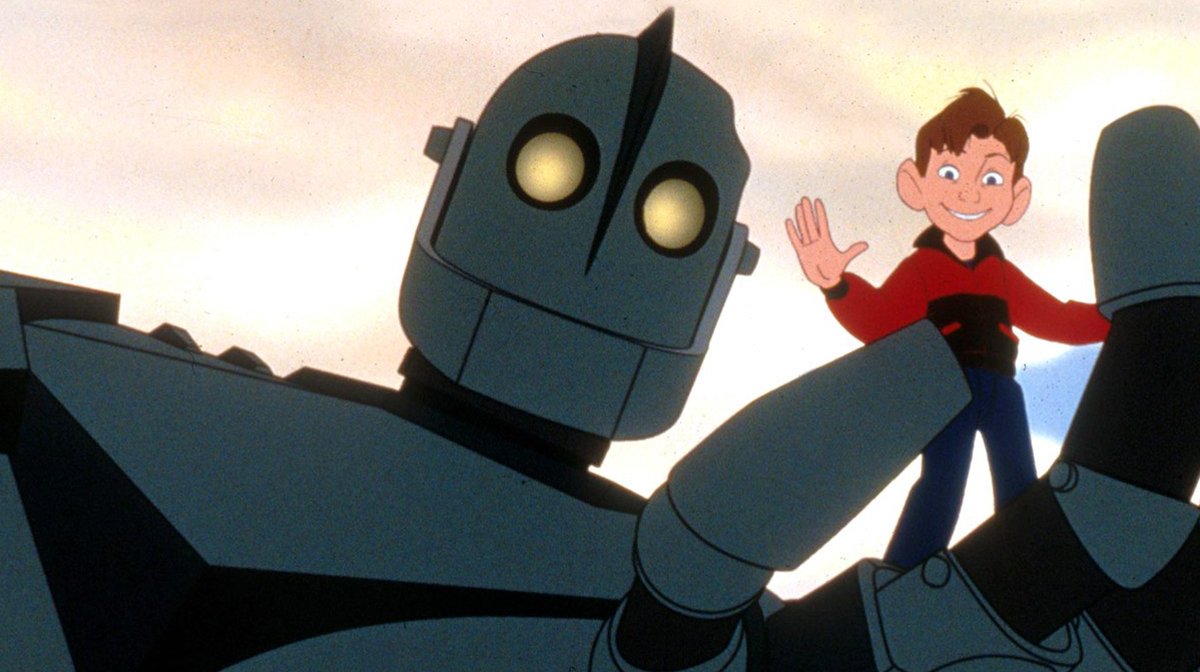

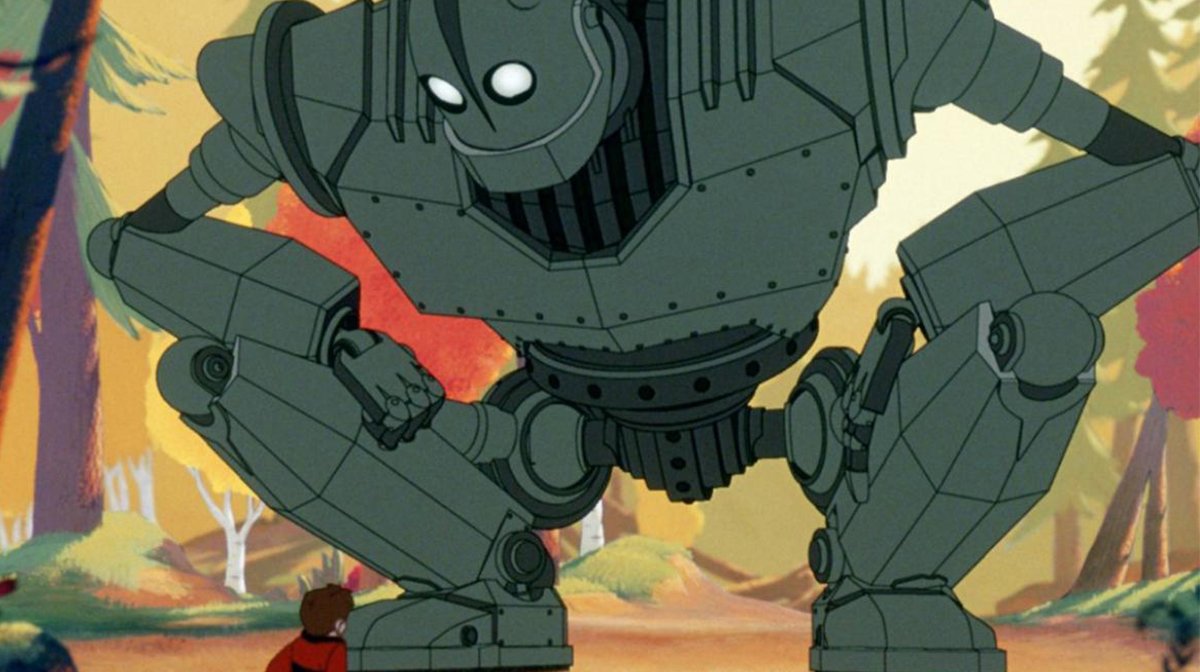

The Iron Giant is a recognisable figure for people born in the early nineties and onwards.

It’s a huge lumbering giant made of metal, with eyes that open and close like doors on a futuristic spaceship. It’s an alien that barely speaks any human language, but has a fondness for eating metal.

And according to Rotten Tomatoes, it’s one of the most highly-rated animated films of all-time.

Warner Bros.

It’s the film that put Brad Bird, the director of The Incredibles and Ratatouille, on the map.

Both of these later films had a fairly wide cultural impact at the time of their release, but none of them have as much cultural cache as The Iron Giant. The question is, why?

The reason, at first, seems quite simple. The film is emotionally resonant enough to stick with kids, and intellectually rigorous enough to appeal to adults.

Warner Bros.

But it’s more than that. Although the film has a distinctly all-American feel, in terms of thematic content it has more in common with the anti-war movies of Studio Ghibli (think The Wind Rises and Porco Rosso).

There is a sense of adventure in those films, and narrative thrust, but all of those things are underscored by the mood of a nation in a specific period of history.

The most impressive thing about The Iron Giant though is the craft. Among western animation it has a unique style.

Warner Bros.

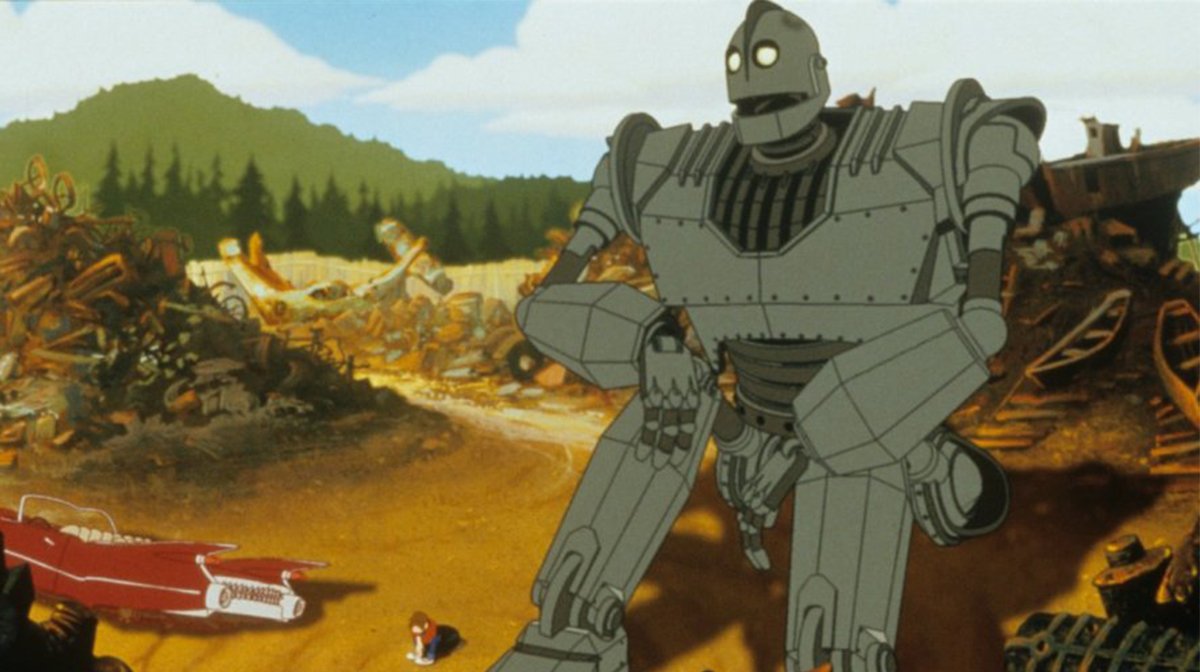

Although they used CGI, aside from the titular giant a lot of the characters and landscapes look hand-drawn, and it’s because the film’s initial photography took place in Maine (the film itself is set in a fictional town from the state called Rockwell).

Because of that research the film looks like it was borne out of the 1950’s, right down to the costume design. The only difference, of course, is that the film is in colour.

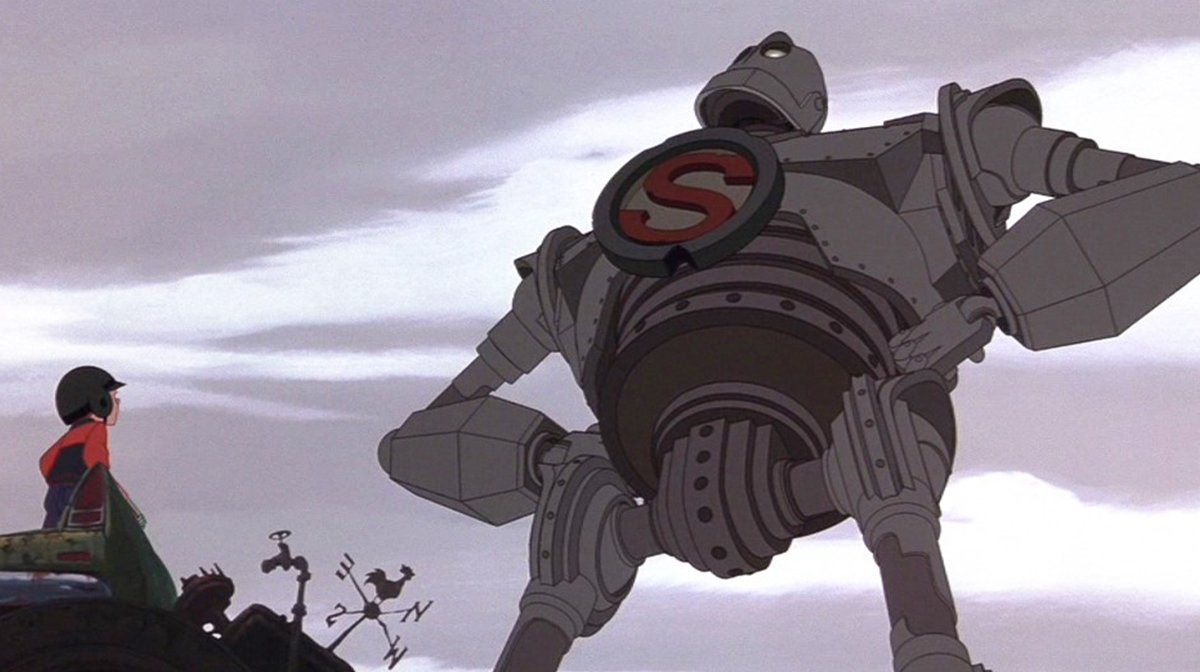

But the effort didn’t stop there. The thing most people remember fondly about The Iron Giant is the wit and heart woven into the script’s narrative.

Warner Bros.

Although it’s a film that deals with fairly serious themes, The Iron Giant is often light and witty, with clever physical comedy scenes and wordplay, aside from the emotional ending.

The overall message of the movie is different to much of American cinema too. The Iron Giant is a metaphor for the outside world, and mainstream American animated cinema at the time had a tendency to look inwards, and be concerned with insular national issues and reluctant to tackle the heady, complex themes the way The Iron Giant does.

The ending always had to be happy, and there could be no threat of real-world conflict or destruction, whereas in The Iron Giant it’s a constant looming threat.

Warner Bros.

There are a number of reasons The Iron Giant is a memorable entry into the western animated canon, but the main ones are its unique outlook and story in the midst of a culture which celebrated sequels and big franchises.

It was a film made with real heart and dedication to the craft of animation.

It may not have the faux-realistic sheen of its Pixar contemporaries, but that’s not the point. The Iron Giant is supposed to reflect real life as best it can, and it does that better than most.