The animated film Chicken Run is celebrating its twentieth anniversary this year!

Released in 2000, this hilarious and poignant children’s film is not only an elaborate play on the classic joke, “why did the chicken cross the road”, but also a commentary on the ruthless capitalist machine, and how female friendship and ingenuity is powerful enough to fight back.

Yes, the chickens knit and crack (get it) lots of poultry-based jokes, but it is a film that believes its audience, adult or child, is intelligent enough to enjoy its comedy and understand its deeper messages about the cruelty enacted under capitalism.

DreamWorks Pictures

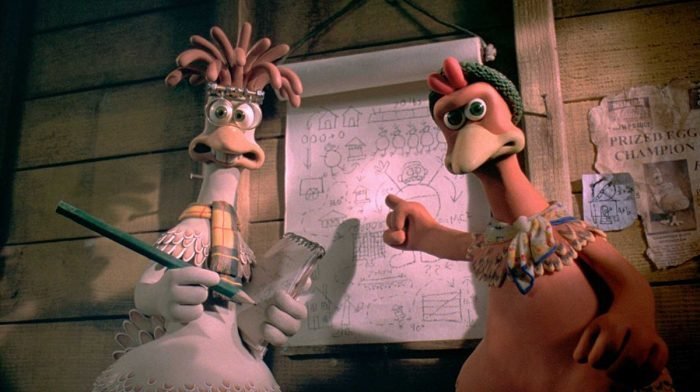

In Chicken Run, lead chick in charge, Ginger, is constantly working on plans to help her and her fellow chickens escape the Tweedy family farm.

To Mr. and Mrs. Tweedy, these chickens are merely a method for making money; they are not pets or equals, but rather a site of production.

And only female chickens lay eggs, a commodity that brings in the capital.

DreamWorks Pictures

This relationship is best illustrated in an early scene where Mrs. Tweedy is checking the egg production record. If a chicken isn’t producing, they are quickly taken away and killed for food, which happens to Edwina the chicken.

When she is no longer providing capital, she must be made useful in another way: nourishing her ‘masters’. While this may seem like the normal order of operations on the farm, Chicken Run is told from the perspective of the chickens.

Edwina’s death is yet another loss of a comrade, a stark reminder that they are only as good as what they can produce.

DreamWorks Pictures

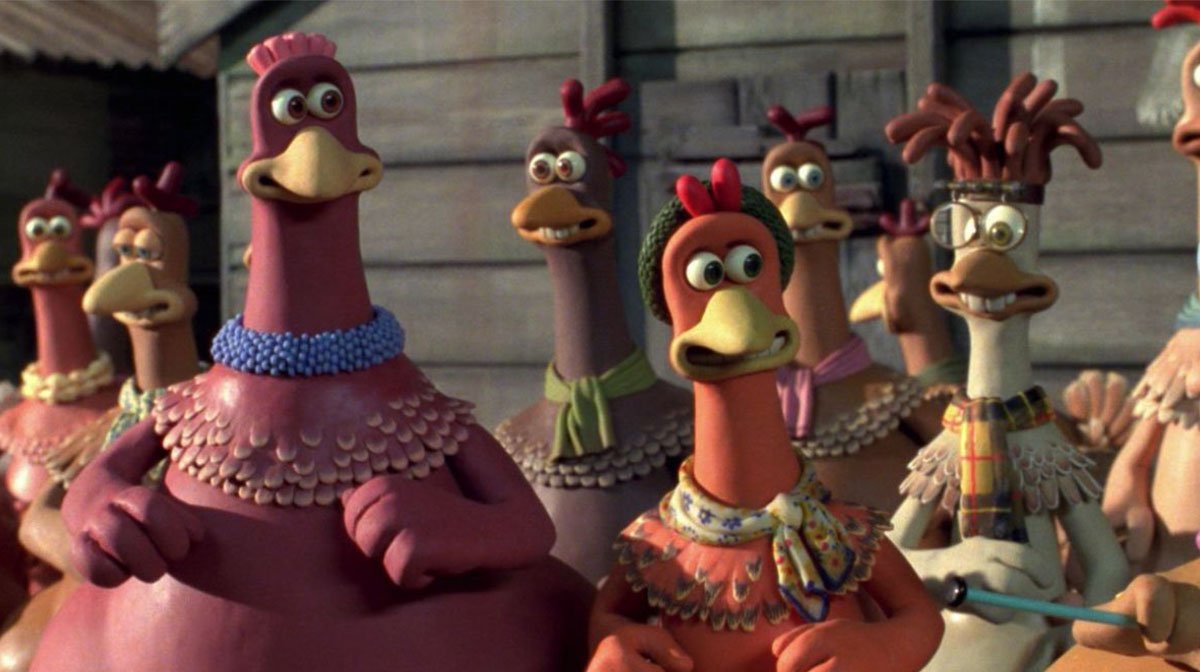

In this group of chickens is their leader Ginger, who lights a fire under her fellow chickens to get them motivated and excited for the possibility of freedom.

She knows how to talk to them, how to get them fired them up, and how to keep them dedicated to the cause. Her passionate leadership is contrasted against the aging rooster, Fowler, the singular male figure who spouts stories about his days in the military but can’t do much else.

While he seems to think he is an authority, he is a talking head, a figure full of hot air and no real vision. Ginger is the one who inspires and pushes the flock forward towards something positive.

DreamWorks Pictures

Ginger is supported by chickens like Mac the scientist, Bunty, Babs, and more. Each of these chickens has a special skill that makes them crucial to the survival of the group.

Mac is able to devise schematics and mechanical plans. Babs can knit and sew. Bunty is a strong supportive force who speaks her mind. While she mostly stands behind Ginger, she is never afraid to voice her opinion and make herself known.

There is no passivity within this flock. It is a group of strong, intelligent female characters who are starting a revolution.

DreamWorks Pictures

Their intelligence shines through their ingenuity. They use eggbeaters to drill through dirt, spoons as shovels, rollerskates as a way to maneuver through tunnels, and more.

They are creative with what chickens can acquire and operate, even bartering with rats to get tools. Nothing can put a damper on the flock’s creativity despite their constant failures. Escape or die are their only options.

Then, a rooster comes to the farm, an American rooster named Rocky who boasts that he is able to fly.

DreamWorks Pictures

Rocky the rooster is from the circus, and he is also used for monetary gain by humans. Whilst he is in a similar boat as the chickens, he is ultimately a fraud who makes false promises.

His appearance makes him seem like he’s the male saviour, the one who can help get these female chickens organised. But really, Rocky is a tool to show Ginger that they are capable of saving themselves. They do not need a suave American rooster to tell them how to survive.

While the introduction of a male rooster is a catalyst for their escape, the importance of female friendship never waivers. Without the bond between Ginger, Mac, Bunty, and the rest, the flock would never have been able to come together and execute such a wild plan.

Yes, Rocky provided levity and something to fawn over, but the female chickens were the ones who ultimately created and executed their own escape.

DreamWorks Pictures

The gender dynamics of Chicken Run extend into the human realm, as well, with Mr. and Mrs. Tweedy. While Mrs. Tweedy is presented at first as stereotypically feminine in a frilly pink dressing gown and slippers, she is the one who runs the farm, not her husband.

She manages the finances, the numbers, and the overall economic well-being of the farm, which breeds cruelty. Her cruelty is fed by the need to make more than what she calls “minuscule profits” – the need to make money and keep their farm afloat.

While she is the film’s villain and is responsible for the destruction of the chickens, she is also a symptom of the larger system of capitalism. She is motivated by the need for money, which she needs to survive.

DreamWorks Pictures

Again, like the chickens, Mrs. Tweedy’s quick thinking is contrasted against the idiocy of her husband, Mr. Tweedy. He follows her without question, giggling at his own jokes and never quite able to keep up with Mrs. Tweedy.

She thinks of ways to make more money, such as making chicken pies instead of just eggs, while using her husband as free labour and someone who can handle the grunt work.

Even in her greed, Mrs. Tweedy does exemplify female ingenuity, and the struggle to fight against the larger capitalist system.

DreamWorks Pictures

Under the bright colours and bold animation of Chicken Run lies a tale about the strength of female friendships and the power of female ingenuity, particularly in the face of fighting back against the destruction of capitalism.

While kids may laugh at the slapstick, adults will laugh at the film’s sharp wit and more political themes. Chicken Run is the feminist animated masterpiece that every child needs to watch, and every adult needs to rewatch.

For all things pop culture and the latest news, follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.